ACADEMY & GALLERY

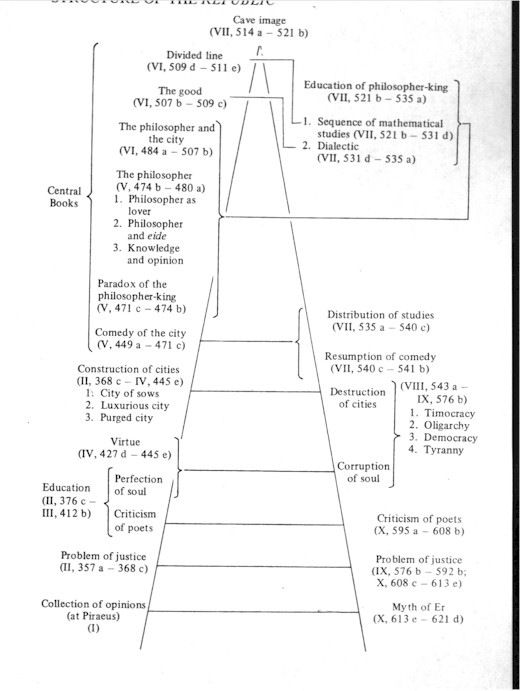

2007 by Lawrence C. Chin. Aim and organization of the Republic The metaphysical core of Phaedo -- the "theory" of form as the investigation into the nature of reality and the concomitant discourse as to the nature of the soul -- is geared toward philosophy as the second mode of salvation -- in the other, transcendental world, so to speak: the world of eternal conservedness. From that discourse, however, as we have seen, the issue of justice for the sake of existence in this temporal world governed by the coming and passing of entropy process has already disengaged. The Republic (Politeia) is a theory or philosophy of order (i.e. justice) for this world, in contradistinction to the other worldly orientation of Phaedo. This disengagement of justice, this shift of focus from major to minor salvation, represents one of Plato's two new aims by the time of the Republic, that "of demonstrating the great advantage of leading a philosophical and fully virtuous life quite apart from the posthumous rewards that those who lead such a life will eventually receive in another world." (Richard Kraut, ibid., p. 10.) The other new aim concerns the saved soul's relationship with those not yet saved, the philosopher's relationship with the rest of the human community: the salvational state of mind, the grasping of the form of the Good, the "contact with an otherworldly realm, so far from making [the philosopher] unfit for political life, will enable [him] to be of immense value to other members of the community" (ibid., p. 9). The worldly reflection of eternal salvation, i.e. "justice", is not only good for oneself in this life, but even good for one's patrie. It is to be noted that justice (dikaiosune), with Plato's differentiation which is common during the axial age, refers to order. It is quite different in meaning from the "justice" of modern analytical philosophy in the English-speaking world -- such as in John Rawls' Theory of Justice. The great advantage of the philosophic and virtuous life and the benefit of it to the community -- justice on the microcosmic level of the Person and on the macrocosmic level of the Corm -- are "the right order of man and society" which is "for Plato an embodiment in historical reality of the idea of the Good, the Agathon. The embodiment must be undertaken by the man who has seen the Agathon and let his soul be ordered through the vision, by the philosopher" (Voegelin, Order and History, vol. III, Plato and Aristotle, p. 47), who can then transmit the order to his community ("the philosopher-king"). It is for this reason, the centrality of the vision of the Agathon, that the discourse of it is located in the center or the peak of the work, as shown in the outlines of the Republic given by Voegelin and Sallis (below: Appendix; the outline of D. Guerrière is more useful for those who are going through the entire narrative of the Republic). We have already given a complete analysis of this central or peak region regarding the "embodiment of the idea" -- the nature of ideas or forms, the Agathon, the divided line, the cave image, the education of the philosopher -- and shown what their modern equivalents would be if the Platonic project should be repeated in the modern perspective. Outside this "metaphysical core", Voegelin may be cited at length to provide an overview of the organization of the Republic as a whole:

Voegelin is as usual masterful in describing the motivating experience of transcendence which Plato expresses with the construction of the ascent in the main body and its framing on both sides by the symbolism of descent in the Prologue and the Epilogue that is modelled on Odysseus' descent into the Hades. The mystical experience of transcendence, in which Plato "resists the spiritual death and disorder of Athens" (ibid., p. 61) and brings up or down the truth of existence concerning the right order of existence in an attempt to save Athens, is paradoxical in that "the truth brought up from the Piraneous by Socrates in his discourse, and the truth brought up from Hades by the messenger Er, are the same truth that is brought down by the philosopher who has seen the Agathon. We are reminded of the Heraclitian paradox (B 60): 'The way up and the way down is one and the same'" (Voegelin, p. 60). For Voegelin's laying-out of this motivating experience behind the construction of the Republic, see "The Way Up and the Way Down" (p. 52 - 62), "The Zetema" (p. 82 - 88; "the experience of the depth and of a direction from the depth upward"). Here we will only add the reminder that the peak of the experience of transcendence is the moment during which the philosopher becomes certain of the salvation of his soul after life (its blissful existence in the divine, or the eternal conservation of its pure order) and that the truth of the right order of existence is the downward reflection (i.e. side effect) from this peak. Below, we will concentrate on the problem of justice as appears in the Republic, together with its historicity, in light of the second half of this reminder: how the ordering force which the salvational pursuit -- the "expectation of catharsis through death" (ibid., p. 14) -- produces in the soul during life constitutes "true happiness" and can even be harvested for the ordering of the entire human world and for use in other worldly affairs. While John Sallis' commentary has been more helpful in understanding the "metaphysics" of Plato, here Eric Voegelin's will serve as the principal guide in understanding this philosophy (or science) of order of Plato's. The background for the problem of justice in the Republic: resistance against sophists' corruption of the soul and society In tribal society the order of society -- "justice" -- is maintained by reciprocity: the equilibrium between giving and receiving (the exchange of gift and in marriage), pain and pleasure (the evil-doer will get what he deserves), fortune and misfortune ("karma"). At this stage the experience of "justice" encompasses both its mechanism (the cultural mechanism of reciprocity and the natural mechanism of equilibrium) and the result of the mechanism (order: supraorganismic internal equilibrium), i.e. it remains undifferentiated. The mechanism in the sphere of culture is known as "tradition", that which the tribal member is taught to regard as sacrosanct and to perpetuate at all cost, lest the society and the cosmos disintegrate into chaos. The compactness of the experience leaves room only for an unconscious practice of "justice" and a blind respect for tradition, that, somehow, it is the source of social and cosmic order, though how it is no one can really bring to words. Such is how myths guide. The characteristic of tradition is that any individual member has to be altruistic and practice self-denial in order to maintain the order of the cosmos and of society, on which the satisfaction of one's own needs are ultimately dependent, however. Since tradition makes possible a harmonious community and social life altruism is praised -- both for its intrinsic worth (the order of oneself is precious, along with the macrocosmic order of society and the cosmos: see "The Thermodynamic Origins of Good and Evil" -- and both engender such respect as to figure as ends in themselves: "existence in form of the cosmological myth") and for its utility in establishing social order (e.g. Chris Knight's theory). The differentiation of consciousness during the Axial Age however dissolves the meaning of tradition and the belief in the natural mechanism of equilibrium of fate (the equilibrium between pain and pleasure, which has conditioned karma thinking and deterred evil-doing, and which still finds echo in Eliphaz's comforting words for Job; J. 4. 7 - 9), and leaves in place an "artificial" society where people see no intrinsic value in altruism, find no natural deterrence against evil-doing, and do not practice reciprocity and do good save to the extent of appearance, seeming (dokein), in order to gain the minimum of praise or social acceptance from others that is required for the satisfaction of one's selfish needs, but deem the pursuit of their own self-interests -- directly or indirectly, by oneself or via others -- as in reality (being, on) the only thing worthwhile. Social order can no longer exist in the form of the cosmological myth, but yet there is no replacement. Society is then artificial because its order is now experienced as desirable only for its consequence of ensuring the satisfaction of individuals' (bodily) needs, the intrinsic value of order no longer holding. The society in such state is apt to fall into chaos at any time. This is the age of the sophist. We have mentioned that the differentiation of consciousness, which carries the collective consciousness of a culture to the next level of development, however always results in both an upward movement, an enlightening effect, and a downward movement, a degenerating consciousness. Earlier the Presocratic physicists and mystics represent the upward movement of differentiation, but, as seen, they are followed by the sophists who destroy their wisdom through fundamentalist literalism and put into expression the general disintegration of people's sense of order and their favoring of seeming. We will presently see examples of this. Voegelin emphasizes that Plato's philosophy must be seen as resistance against this corruption by the sophists, who are thus philodoxos, those who in Plato's work are the exact opposite of philosophos and the disease for which the latter is the medicine. This is a point of special difficulty for the contemporaries since, although the resistance is never successful in worldly terms, i.e. within the history of Hellas (more on this later), philosophy has triumphed spiritually, such that the texts of philosophy are preserved on account of its preciousness to the present day while those of sophism are completely forgotten and lost, with the unfortunate consequence that the context for understanding Plato is lost for the contemporaries. Furthermore, Western philosophy, especially along the Anglophone line, has again degenerated to philodoxy, so that, both factors working together, it becomes exceedingly difficult to recognize that what passes as a "philosopher" interpreting Plato in contemporary academia in the Anglophone world is often just the philodoxer against whom the philosopher fights in classical time (Voegelin, ibid., p. 65 - 7). We have defined the philosopher as the mystic concerned with the salvation of the soul through the love of wisdom, while Voegelin defines him more in terms of the minor aspect of this concern for salvation (minor salvation): the philosopher is "the thinker who advances propositions concerning the right order in the soul and society, claiming for them the objectivity of episteme, of science -- a claim that is bitterly disputed by the sophist whose soul is attuned to the opinion of the society" (Voegelin, p. 69). The two sides complete the definition. Plato represents the continuation of the upward movement of the differentiation of consciousness that is temporarily broken. The earlier remarks regarding Plato's motivating experiences must be seen in the light of this resistance against corruption or degeneration of the Athenian polis: the mystical experience of transcendence is on its reverse side the experience of endangerment by the corrupting society around (p. 84). Minor salvation -- the salvation of the soul in this life -- for Plato at this point of his development is thus tied up with the larger problem of the salvation of the polis (the human community) rather than being entirely a personal affair. The salvation of the Athenian polis is the purpose of the Republic. The strategy of communal salvation is the projection of the salvational state of the soul -- the politeia of the Person, i.e. the right order of the soul (Voegelin, p. 87) -- onto the organization of the human community or polis -- the politeia of the Corm -- in accordance with microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism (what Voegelin refers to as the "anthropological principle"; p. 86), to result in what may in a shallow understanding of Plato be called the "political philosophy of Plato". It is in view of this task of the "persuasive imposition of right order on unruly passion" of a disordered society against the resistance of the latter that Plato employs the symbolic form of the dialogue. Resistance implies opposing psychic forces and the drama of the dialogue captures the tension between the opposing forces of the Athenian society representing sophistry and disorder and the Socratic personality representing divine wisdom and order. Previously it was the Aeschylean tragedy which personified the "drama of the soul", "the forces of the soul... in the struggle for the order of Dike." Presently, the Platonic dialogue "forms the successor to Aeschylean tragedy under the new political conditions" (Voegelin, p. 11). "Only when the tension of conflict has subsided and the new order is established can [philosophia's] expression assume the form of a static dogma or a metaphysical proposition" (ibid.) such as is the case with the post-Platonic philosophy. We must mention in the outset that Plato's project of the salvation of the Athenian polis was a failure, and we will not seek here a contemporary equivalent model of some philosophically educated physicist re-ordering society according to the physical laws of nature in order to save it, which is as much absurd as will surely end in failure. In the context of resistance, then, the Republic begins the discussion on justice -- the means for minor salvation -- from the oldest to the youngest. Cephalus is a relics from that previous time of the unconscious practice of justice; he respects "tradition" as the source of order without knowing why it is. He "furnishes an instance of the man who leads a reasonably righteous life and is willing to compensate for the minor offenses he committed by means of his wealth. He represents the 'older generation' in a time of crisis [i.e. of differentiation], the men who still impress by their character and conduct that has been formed in a better age. The force of tradition and habit keeps them on the narrow path" -- hence Cephalus, now old, worries about karma, his fate in the afterlife, that is, the belief in the natural mechanism of equilibrium is still active in him -- "but they are not righteous by 'love of wisdom'" -- knowing how order in life and society is produced and the reason for the natural equilibrium -- "and in a crisis they have nothing to offer to the younger generation which is already exposed to more corruptive influences.... [T]he men of this type are the cause of the sudden vacuum that appears in a critical period with the break of generations" (Voegelin, p. 57). Note with Cephalus we clearly see the justice of citizens and by extension of society entangled with the former's salvation after life (major salvation). The justice of citizens will here be differentiated into minor salvation proper after the differentiation of the justice of society into communal salvation fails, as shall be seen. The salvation of the polis proceeds by exposing, via the search for the eidos of justice, the underlying condition for the production of order and re-establishing, via the re-integration of the human and the cosmos, the intrinsic worth of social order in the communal consciousness (Geist in Hegel's word). Unconscious, and with his vague, unreflected traditional notion of justice as reciprocity (paying the debts owed to others and performing the sacrifices owed to gods), Cephalus cannot be taught, however; so he leaves the scene. (Or, as Alan Bloom has it (Interpretative Essay in the Republic, p. 312), the ancestral code represented by him cannot be attacked in his presence, though it must be attacked in order for justice to show itself in its nature.) Next, in this search for the eidos of justice, Socrates debunks (differentiates and dissolves) just this original, compact and vague notion of justice as reciprocity ("it is just to give to each what is owed", so named by Simonides), this time proposed by Polemarchus from the middle generation and which now is only the superficial and occasional appearance of justice. Polemarchus then offers the modified notion (from "it is just to give to everyone what is fitting, and this [Simonides] names 'what is owed'" [...oti tout'eih dikaion, to proshkon ekastwi apodidonai, touto de wnomasen ofeilomenon; 332 c2] to "justice is doing good to friends and harm to enemies" [to touV filouV... eu poiein kai touV ecqrouV kakwV dikaiosunhn; 332 d7]). This does not work out either. After Polemarchus Thrasymachus cuts in to propose his version of justice: justice as the advantage of the stronger.

Thrasymachus being the sophist present in the scene, this "radical" notion of "justice" of his is the first example of the expression of the corruption of Athenian Geist. The underlying presupposition of this (and later) expression(s) is the valuation of wealth -- and so of consumption or the pleasures thereof -- as the greatest -- if not the only -- good. Thrasymachus is basically saying that we all want out of life nothing more than resources with which to give pleasures to the body, and that we thus attempt to enslave one another to obtain these resources -- the reason to be strong and master over others and to have power -- and then cloak the resultant master-slave relationship with the name of justice, with right-and-wrong, in order to keep the slaves subordinate. This only seems common sense to us and to the masses of the Axial Age because bodily pleasures have become the only type of pleasures, the only good, around which self-interest can revolve: a sort of hedonism. But what if consumption and bodily pleasures are not good, let alone the only good? What if the ruler's (or the community's, when one democratic polis attempts to enslave another polis) pursuit of self-interest is actually not bringing advantages to himself (or to itself), but harm? As shall be seen, in light of the tripartite structure of the soul, the ruler (or the community) is satisfying only the lowest component of his soul (of its composition) -- the appetitive part -- to the complete neglect of the two higher functions of his, and Thrasymachus' justice is in fact not justice at all, but injustice: the ruler is just the tyrant in his city (and the city the tyrant within the league). Socrates is going to show later how the tyrant, as such, is precisely not bringing good to himself at all, but only harm. The corruption is based on an erroneous understanding of what really is good. At this point Thrasymachus could have responded in two ways to Socrates who debunks him by pointing-out the uncertainty involved in this attempted definition (eidos) as to what actually constitute advantages or "good": (1) justice (actually injustice) be redefined as only apparently bringing good to oneself (Polemarchus' contribution); and (2) the ideal ruler would know what is really good for himself and thus would be really bringing good to himself (Thrasymachus' insistence). But, as we shall see, Socrates will demonstrate that what is really good for oneself can only be practicing justice, i.e. being an orderly person and not a slave to wealth-acquisition and an addict to bodily pleasures. Thrasymachus' position would thus become theoretically impossible. We see here how Cephalus as the older generation and Polemarchus as the middle generation "cause by their emptiness of substance" -- exposed via the differentiation of consciousness -- "the vacuum in which dangerous figures like Thrasymachus can exert their influence unchallenged. The sequence of Cephalus, Polemarchus, and Thrasymachus dramatizes the aetiology of decline to the point where the crisis becomes articulate in the sophist [i.e. Thrasymachus] who proclaims his disease as the measure of human social order". (Voegelin, p. 71). The Athenian society is now the sophistic soul written large (the macrocosmic version of the microcosmic sophist); this is the essence of its corruption. As the souls of the younger generation such as Glaucon and Adeimantus, though longing for a true understanding of order and justice, are crushed by the sophistic environment around to accept its version of justice, they cry out "de profundis to Socrates the helper" (Voegelin, p. 81). Thus, next, Glaucon shows Socrates another scenario about the origin of justice he has learned from the sophists, and which is therefore the second example of sophistic justice, a second variant of the eclipse of the higher functions of the soul by the base, appetitive function:

So, justice originates "as a result of weighing the advantages and disadvantages of unregulated action; after due consideration justice will be pragmatically honored as the more profitable course" (Voegelin, p. 74). People no longer believe that, as a matter of natural laws, the righteous will reap the fruits of his good works and the evil-doer will get what he deserves. This "social contract" comes to replace this traditional belief; it is the direct consequence of everyone's pursuing the way of the tyrant. In Thrasymachus' notion of justice, as everyone pursues bodily satisfaction as the only good, and becomes thus engaged in master-slave struggle with everyone else, one (in the tyrannical system, or a small group in oligarchy, or the majority in democracy) emerges as the master who exploits the rest who are weak for such satisfaction of his. In Glaucon's scenario, all reach a stalemate with one another in such struggle, and thus decide on a compromise: the two possible outcomes of the same struggle which the seventeenth and eighteenth century theorists term the "state of nature". Take note of the condition of nature such that the satisfaction of bodily desires always requires things and people external to oneself and rests upon their exploitation -- hence involves overcoming resistance, of other people especially, so that the acquisition of power (the ability to implement one's will and objective even against the resistance of others, the ultimate form of which is tyranny) is always the avenue to such satisfaction. (Recall the earlier exploration of the origin of karma thinking (1. 1. 2. "The Origin of the Elements of Primitive Religions") which reveals the primordial human condition that doing wrong to others brings pleasures to oneself, but then entrains, for the functional perspective, the recompense of others via their pleasure at one's own suffering.) Aristotle later is to make much of the dependence of bodily desires on external instrument for fulfillment. Injustice, then, tends to better satisfy a person's bodily needs and wants than does justice, bringing more pleasure to life. This then leads to the doxa of the greater advantage and profit of doing injustice, that the unjust man is happier than the just man -- if the former does get away with his injustices -- and that justice is someone else's good and one's own loss (392 b): the doxa which underlies both Thrasymachus' notion of justice and Glaucon's scenario of its origin. Thus, the current doxa is produced by the eclipse of the soul by appetite, of its higher function by its lower function, under the condition of nature regarding the satisfaction of bodily pleasures. It is however also brought into being by the disintegration of the belief in the natural equilibrium of fate and the loss of the spirit of reciprocity (seeing intrinsic value in it) which elsewhere motivates the Golden Rule (of the New Testament and Confucius) and the contemporary understanding of fairness (e.g. the stage six of Kohlberg's moral development schema or John Rawls' theory of justice). After all, society can still be in good order despite the pre-dominance of appetite, if everyone respects the rule "I gratify you and you me." The nihilists and dis-believers in equilibrium emerge during the Axial Age together with the atheists -- all so horrify Plato and Buddha alike -- due to the general differentiation of consciousness. The disintegration of the consciousness of equilibrium of fate, justice, and reciprocity that is seen here in Thrasymachus' notion of justice and Glaucon's "social contract" scenario represents the degenerating consciousness during the age of differentiation. While philosophy is constituted in the upward movement, the disintegration and degeneration at issue here dissolve the traditional value of reciprocity, leave bodily pleasures as the only good (hedonism1), and result in the nihilist opinion of the multitude (the doxa).2 After Glaucon Adeimantus further elaborates on the doxa of social contract by pointing out that "parents admonish their sons to be just, not because justice is a virtue in itself, but for the sake of reputation and social success that will be gained by just conduct (362 e - 363 a)" (Voegelin, p. 80). This leads to the split between appearance and reality, between dokein and on. That is, one does not want to be just, unprofitable this course is, but to appear just. The appearance of justice, its reputation -- and no more than this --, as hinted at, is a further profitable course because under the social contract scenario the multitude will think it less likely to suffer injustice by him that is believed to be just and will consequently crown him with power -- from which position he can then further satisfy his bodily desires! This paramount problematic of the split between appearance and reality which runs through many of Plato's dialogues as one of his chief targets, thus results when the original compact order of society is differentiated down to the skeleton of a social contract as the only thing that holds the society together, and which holds it together as a mere aggregate, where the individual members pursue only the maximization of bodily pleasures in opposition to others' corresponding desire of not falling victim to this maximization which tends to cut short their own maximization.3 The second doxa concerning the contractual origin of what is known as justice, with the split between appearance and reality that it brings with itself, is problematic for the philosopher in that, reflecting social degeneration, it does not "penetrate to the essence of justice as the greatest good and of injustice as the greatest evil" which is the primordial human experience -- in the intuition of thermodynamics, as we have asserted: that justice is good because it means order, which is sustained on the cosmic and social level by rituals and sacrifice and the altruistic behavior of the individual members, and on the personal level by ascetic practices (e.g. sweating, abstinence before hunting), and that doing things conducive to social order is happiness -- both for the benefits to one's own order and for the future pleasures guaranteed by the law of karma. That is, the primordial experience of order is forgotten along the downward path of differentiation. "That the doxa leaves them in the dark about the essence of justice is the grievance of the young men" such as Glaucon and Adeimantus; "they implore Socrates to show them why justice is good in itself and not only a good in relation to reputation, honors, and other worldly advantages" (Voegelin, p. 73). Socrates' task here is then the recovery of the primordial experience within a newly differentiated consciousness. This is his role as the physician for the Athenian sickness: the philosopher-physician is another symbolism running through many of Plato's dialogues. In order to do so under the weight of the preceding doxa, "in order to arrive at a proper understanding of the issue the two types, the unjust and the just man, must be assumed in their extreme purity" -- such is the method of thought experiment Glaucon proposes -- "The unjust man is assumed to be a master of his craft, a man who will commit his unjust acts so cleverly that he will not get caught but, on the contrary, gain the reputation (doxa) of justice; and if he should get into a tight spot he is assumed to be equipped with the necessary ruthlessness and connections to extricate himself from it, again with the appearance (doxa) of perfect justice" (p. 78). The most perfect injustice is thus to seem to be just while not being just (εσχάτη γαρ αδικία δοκειν δίκαιον ειναι μη οντα), and the most perfect unjust man is he who does the greatest injustices (thus giving himself [i.e. his body] the greatest pleasures) while having provided himself with the greatest reputation for justice (thus without incurring others' retaliation: εατέον τα μέγιστα αδικουντα την μεγίστην δόξαν αυτωι παρεσκευακέναι εις δικαιοσύνην; 361a 8 - 9). "The just man, on the other hand, is assumed to be pursued by the reputation of injustice because, if he were socially successful as the result of his justice, we would not know whether he is happy because of his justice or because of the honors and rewards" (Voegelin, ibid.). The most perfect just man must then be he who does no injustice (thus forgoing the bodily pleasures that are otherwise available to him), yet has the greatest reputation for injustice (thus providing occasions for others to recompense themselves with pleasures at his expense): this is the most radical split between appearance and reality, so that the just man's justice may be put to the test to see if it is softened by bad reputation and its consequences... (μηδεν γαρ αδικων δόξαν εχέτω την μεγίστην αδικίας, ινα ηι βεβασανισμένος εις δικαιοσύνην τωι μη τέγγεσθαι υπο κακοδοξίας και των υπ'αυτης γιγνομένων; 361 c 8 - 9). Now then judge which of the two is happier. Almost all would consider the perfectly unjust man to have gained more profit and advantages from doing injustice -- and so to be happier -- than the perfectly just man from doing justice. Glaucon is here demonstrating, within the context of the forgetfulness of the intrinsic value of order and the law of karma, that justice and injustice, like all things perhaps (except for happiness, undeniably -- see the discussion of Aristotle below), have no rewards or attraction intrinsic to themselves but depend on their consequences for their relative attractiveness to the practitioner, and that, given that, as implied in the "social contract theory", the benefits of just actions are for others only and none for the doer, while the reverse is true for unjust actions, the seeming (doxa) of justice in combination with the reality (being: onta) of injustice is the most beneficial to and exerts the greatest attraction for the practitioner. We emphasize once more that this works only when the appetitive part of the tripartite soul is the only one active -- the pursuit of consumption (and sex: i.e. of bodily pleasures in general), whose thermodynamic index is, again (c.f. Hesiod's Work and Days), that injustice is easier to do, whereas justice is hard, a drudgery (επιπονος), to be practiced only for its good consequences (wages and reputation, which bring influence over others, i.e. create "social capital", so as to secure more resources for better satisfaction of one's bodily desires) -- if in fact these should follow, and they do not in the above case of the most just man. This index -- the thermodynamic downward path, that of dissolution: in this case, that of the order of the soul -- further magnifies the attractiveness of injustice and the unattractiveness of justice: the common-sense or doxa therefore prefers injustice to justice not only because the former better satisfies bodily desires but also because it is far easier to do; it thus can only imagine justice as the product of a compromise between people who would otherwise all dream of possessing the ring of Gyges. As Eric Voegelin analyzes:

The European Enlightenment repeats the same crisis in the experience of order:

The disintegration of the universal order or realissimum during the Enlightenment is also due to the differentiation of consciousness that is, to be sure, differentiating a new truth about order, that of universal equality under the type called nation-state. (See The Origin of Feminism in the Differentiation of Subjectivity.) Hobbes' aside, the more temperate Lockean social contract scenario underlies this new truth of order. The reproach about this new, "modern" order concerns the divorce of the Person and society (supraorganism, Corm) from the natural cosmos that serves as the milieu of their existence. The human order is now an artificial creation that is not part of the life of the cosmos: the same problem with Glaucon's social contract society. Both contrast directly with the old, traditional, cosmological order, as noted (ftnt. 2). The upward work of Plato is to re-integrate the human order -- the soul -- into the cosmic order, as shall be seen. The Enlightenment's repetition of doxic sophistry is not just caused by the differentiation of a new order of nation-state. The study of Foucault's late work ("bio-power") has taught that the nation-state in formation, in its need to objectify and exploit its population as natural resources in order to increase its competitive edge, has intentionally shifted the measurement of the Person away from "soul" and its spiritual functions toward the physical force each may contribute to the mechanism of the state. The nation-state has thus purposely created a culture in which only the appetitive, along with the honor-loving -- not the intellective --, functions "count." Metabolism, health, living-standard consequently become the only concerns of importance, to the complete neglect of wisdom. Thus begins "the unmitigated pursuit of the goods connected with the body and the city which characterizes the traditions begun by Machiavelli and Hobbes" (Bloom, ibid., p. 397). In this way the Enlightenment becomes the perfect parallel of the age of the sophists that precedes the fulfillment of the Axial Age. Now hard to practice though justice may be -- there is no argument in this -- Socrates will show below that most people are wrong in judging injustice as providing greater profit and advantages and the unjust man as the happier. This is the path toward "re-integration." It is precisely by hint of the thermodynamic index of justice and injustice -- the upward path of order-formation and the downward path of order-dissolution -- that Socrates is going to present a different consideration of the relative attractiveness of the two. The most unjust man appears happier than the most just man only when, as said, happiness is restricted to being a function of the satisfaction of the lowest component of the tripartite soul, the appetite. Only in relation to the satisfaction of this function does "seeming to be" appear more important, more desirable, than "to be". For those in whose soul the higher, intellective component is predominant, the nature of happiness changes, and the "profit" in doing injustice ceases to be profit at all. So, Glaucon charges Socrates to save justice in face of the overwhelming power of opinion in regard to the profitability of injustice, to explain how justice can possibly be desirable in itself regardless of the reward ("wages", misqoV) and reputation (doxa) it may beget -- how it should be done even if no one and no god would know about it; how, even more, "justice is among the greatest goods -- those that are worth possessing for their consequences [i.e. profit and advantages], but much more for themselves."4 Glaucon asks Socrates to "praise this of justice, that justice is profitable to the [soul] having it and injustice does harm, and leave wages and reputation aside for others to praise." (367 d) This is the problem of the possibility of minor salvation, insofar as Socrates' main argument will consist in firstly identifying justice as order and the just person as possessed of a well-ordered soul, then in demonstrating that this orderly state of the soul begets the greatest happiness in this life because it is the healthiest, and finally in linking the philosophic life with it as the only path toward such orderly state. "If philosophy is the health of the soul, and hence justice in the highest sense, justice is desirable in itself, regardless of reputation." (Bloom, ibid., p. 397.)

The evolution of the conception of justice The original notion of justice as reciprocity (in the tribal context, just like karma) is here captured for the last time in Simonides' saying: "it is just to give to each what is owed." Plato's strategy and the eide of virtue The axis of the argument is thus the acquisition of the true eidos of justice, the state of order by nature (physis). Plato's use of these two terms further accentuates the philosopher's role as the physician attending to the sickness of the soul that magnifies into the sickness or corruption of society.5 That justice is a certain (the natural, healthy) state of the soul (psyche) means that the eidos of justice (health, order) is embedded within the eidos of the soul -- Plato's understanding of the structure of the soul, advanced since Homer via the intermediary of the Presocratic mystic philosophers. Since the inquiry is conducted within the context of resistance against (or curing of) social corruption, and since, in accordance with the functional perspective of microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism within which Plato operates, "the city is the human being written large" ("... every polis writes large the type of man that is socially dominant in it", i.e. especially the ruler; Voegelin, p. 70), the justice of the Person is sought indirectly via the investigation into the eidos of the polis and the justice embedded therein. (The ostensible reason Socrates gives for this is that justice in the larger entity is easier to perceive.) That is, Socrates is in search of the "magic politeia", namely, the structure which captures not only the inner organization of a person's soul but also that of a polis as a supraorganism. This microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism would still have some validity in an approximate way today, within our differentiated view of society and the universe, that is, in regard to the etiology of social corruption, since Plato is saying via this that the disorder of society is an external reflection of the disease in the psyche of its members. So does also his strategy, since, given so, "the diagnosis of health and disease in the soul is... at the same time a diagnosis of order and disorder in society" (Voegelin, p. 69). The structure or eidos of the supraorganismic unit is not immediately given, but is arrived at through a "symbolic form" analogous, again, with Hesiod's theogony, and which Voegelin has therefore named the "poleogony" (ibid., p. 96). The poleogony lets the structure, or proper relationship among the synchronic components, of the eidos sought for (the magic politeia, the right order of the cosmos, human community, and Person) come into intelligibility through a diachronic succession of their genesis in four stages:

With this, the eidos of a polis -- the truest and the most orderly (most beautiful, kalliston) communal organization -- is arrived at, expressing the right order of the soul of the philosopher "in large letters": the projection of the politeia of the Person onto society, resulting in the communal existence in the salvation state. A most orderly polis as the philosopher's soul written large and embodying the magic politeia to the fullest extent, is the most perfect supraorganism; this city that is best governed (arista dioikeitai) is like a single human being (kai htiV dh eggutata enoV anqrwpou ecei; 462 c 10), with all members blended completely into the whole (the "somatic unity" in Voegelin's words) just as all the cells constituting a multicellular organism are blended so completely into the latter that their individuality is effectively lost.6 This is how the critical label of "totalitarian" gets attached to Plato insofar as the complete group homophone (462) that for Plato alone constitutes right order on the supraorganismic level is precisely how we have defined "totalitarianism" in our thermodynamic interpretation of history. (More on this below.) And insofar as the order of the philosopher's soul is ordered upon the Agathon "in the other (transcendental) world", this city can properly be called "theocratic". Historically, whenever prophetic individuals motivated by the same experience of transcendence as is Plato attempt to realize its "downward reflection" on the supraorganismic scale (ordering society in the present under the transcendent order of God), such totalitarian, at times communistic, theocracy appears, such as the Calvinist, the Puritan, the Anabaptist of John of Leyden, the Amish. (This is when they are considered under the aspect of a self-functioning [autarkes] society. Under the aspect of "cult" within a larger society, they can be seen as the equivalent of the spiritual community that the philosopher founds after his failure to save his polis, i.e. the Academy.) Even the contemporary Islamic extremist or militant evangelical organizations aim at the same. (The actual totalitarian communist or fascist states, however, are degenerate forms of theocracy and so do not figure here. More on this below.) The kallipolis is now opposed to the existent disorderly polis that is the philodoxer's or sophistic soul written large: salvation vs. damnation. It is because the kallipolis is the projection of the soul of the philosopher onto the supraorganismic level that Socrates proposes the famous condition that only if philosophers become kings in the polis or kings genuinely and adequately philosophize can this most perfectly ordered polis come into being and disorders at last be banished from the world (the "third wave of comedy"). "The true order that is real in the philosopher's soul can expand into social order only when somebody with a philosopher's soul imposes it on the polis" (Voegelin, p. 103). In this respect Voegelin emphasizes that "Plato is not interested in forms of government without regard to the animating psyche" (p. 86 - 7); "the goodness of a polis has its source not in the paradigm of institutions" (p. 87) but is the result of the good order in the souls of its citizens, but especially of the rulers. Plato does not wish to give "the false impression that good order in a polis can be created through institutional devices" (ibid.). The same is true of the theocratic designs, just mentioned, that have appeared in history or are in the making right now. This is quite contrary to the condition of the founding of the American constitution or of any modern constitution, where the founders, wary of rulers with disorderly soul, attempt to construct systems whose automatic functioning is precisely impenetrable to the psyche of human beings. Plato loves order, but order radiated from the psyche. But this does not mean that he loves only highly self-conscious order. He admires the primitive polis because it is a human, noosphere equivalent of the bee hive or ant colony in the biosphere, those Arthropods with an absolute, unconscious efficiency in their division of labor and an extremist ("totalitarian") social unity. The poleogony is an example of the complexification of the noosphere in regard to consumption (the satisfaction of appetite), and the beginning healthy polis consumes "mindlessly" but because of this consumes no more than is necessary, a pure and efficient metabolic "body" (not "mind"). The education (paideia) of the guardians that takes place during the third stage of poleogony (elaborated in Book III) is in the same symbolic form, save on the level of the Person, and may thus be called "psycheogony": it concerns the coming-into-being of the right order in the soul. Before being introduced to philosophy, the soul of the guardian is to be formed via mythic poetry, gymnastics, and music. These constitute the traditional Hellenic curriculum of paideia (poetry for the very young, gymnastics for the body, and music for the soul). Poetry as it stands, however, is bad for the order of the soul, the reason for which will be seen later; Plato has Socrates perform a purgation of poetry in the beginning of Book III. As for the exceptional value of music for the formation of the soul: Plato would certainly concur with a contemporary saying: "music is experienced, diachronized, and hearable mathematics" ("Musik ist empfundene, verzeitlichte, hörbare Mathematik", by Hans Zimmermann). Music is thus logon, like speech and mathematics. Music puts the soul (today we say "mind") in order for the same reason for which speech, the study of forms, and mathematics do: through the incorporation of the orderliness of the cosmos represented in music as well as in speech, forms, and mathematics, the soul becomes ordered in like manner. This is Pythagorean, and it works because of microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism; and we will see later that Plato's otherwise incomprehensible numerology is merely the numeral expression of musical tones, which he believes replicates the structure of the cosmos.7 Finally, contrary to tradition, Plato asserts that the purpose of gymnastics is not the training (care: therapeia) of the body, but the formation of the order of the soul (410 c 5). For this reason, it -- with rhythm and harmony recapitulating the orderliness of nature -- should be like simple music (thV aplhV mousikhV; 403 b 5). These are the prerequisites for the final formation of the politeia of the soul through philosophy -- its turning (periagoge) and ascent (epanodos) from arithmetic to dialectic, which has been laid out in the exposition of the divided line -- which will enable its possessor to become the best guardian and ruler. Virtue, and its opposite, vice, are conceptions that appear in the description of kallipolis and form the general context for the discernment of the eidoi of justice and injustice. Manifestly, Plato's conception of "virtue" (arete; or excellence) elaborates upon, or explicitates, the generally Greek conception. Virtue is the function of each thing -- e.g. the eye's ability for or function of sight; it is its work (ergon); a thing's having virtue means that it is in good shape, in good order, so as to perform its function well (353 c). Aristotle further specifies such condition called "virtue" (the "virtuous condition") as the Golden Mean, which Plato implicitly accepts here as well (400 e: as defining eulogia, euarmostia, euschmosunh, euruqmia), and it is what, on the other side of the world, Laozi means by "virtue" (de: 德), also. A thing's lack of virtue, or possessing vice (kakian), then, means that it is in such bad shape, in such disorderly state, as to be unable to perform its function, e.g. the eye's going blind. The four virtues, applicable in the same way to the Corm (polis) as to the Person (the soul), are wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice (sofh, andreia, swfrwn, dikaia; 427 e 10). The kallipolis has the virtue of wisdom because it is "of good counsel" (eubouloV), since its rulers are in the possession of the science (episteme) of order, able to counsel "not about some particular of the things in the city, but about the city as a whole, how it would best deal with itself and the other cities" (ouc uper twn en thi polei tinoV, all'uper authV olhV, ontina tropon auth te proV authn kai proV taV allaV poleiV arista omiloi 428 d); of courage, because the class of guards has the power that through everything will preserve (save: swsei) the opinions (doxai) produced by law about what is terrible and what is not, in face of pleasure, pain, fear, and desires (epiqumia; 430 b); and of moderation, because its smaller class of rulers who are better by nature (beltion fusei) is master over its worse class (tou ceironoV egkrateV; 431 b), the most numerous class of traders, workers, and farmers, in whom desires, pleasures, and pains are accentuated the most (431 c). Moderation (sophrosyne), thus, is not a trait belonging to one particular of the three classes of the polis, but is a condition of accord and harmony (sumfwnia, armonia), in which both the rulers and the ruled (the class of workers and guards) are of the same opinion as to who should rule (431 e). Justice, briefly, is the condition that resides in the polis when it is wise, courageous, and moderate as is the kallipolis. We will turn to this presently in discussing the main proof of the happiness of the just man. Because the whole supraorganism, when each class in it is maximally functional in its virtue, will be in good order so as to be maximally functional, Voegelin calls these virtues "ordering powers", those "which bring order into the field of forces" (p. 108), i.e. the field of heterogeneous and potentially conflicting components.

Adopted from Voegelin, p. 109. Originally from Ueberweg-Heinze, Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, 13th ed., p. 275. The three classes that result from poleogony and the structure of cormic virtues describing the kallipolis mean that the "magic politeia" is a tripartite structure. Socrates arrives at the same tripartite structure in the inquiry into the soul via the phenomena of similar conflicting forces present in a person, such as when some part of the soul desires to drink but some other part -- it must be another part, for no single part can produce opposite actions at the same time -- forbids the person to do so (439 c6) -- the appetitive vs. the calculative -- or "when desires force someone contrary to the calculating part [and] he reproaches himself and his spirit is roused against that in him which is doing the forcing" (440 b). Thus, on the microcosmic level the soul consists also of three interacting parts which correspond to the three classes of the completed polis: the calculating, intellective part, logistikon, characterized by the love of learning and wisdom (filosofon, filomaqeV); the spirited part, qumoV, qumoeideV, characterized by the love of honor and victory (filonikon, filotimon); and the appetitive, desiring part, epiqumhtikon, characterized by the love of money (or simply consumption, sexual and bodily pleasures: filocrhmaton, filokerdeV). The existence of the three social classes or strata in the polis means that, on the level of Corm, there are three types of persons in each of which the respective component of the soul pre-dominates (rules): the philosopher-ruler in whom the logistikon pre-dominates, the warrior-guard-auxiliary in whom the spirited part pre-dominates, and the ordinary greedy money-maker in whom the appetitive part pre-dominates. Moreover, the same sorts of interaction among the three components of the supraorganism as among those of the Person also produce the variety of civilizational types: the Hellenes as a unit of supraorganism are characterized by philomathes, the Thracians and Scythians by thumoeides, the Phoenicians and Egyptians by philochrematon. We will turn to the virtues of the soul in the same discussion of the proof of the happiness of the just man. To note is that the Republic actually does not present a complete picture of the structure of the soul. As revealed in the discourse of Symposium, there is in fact a component extra to the tripartite structure, that of eros, which motivates each component of the tripartite structure to seek after the respective object proper to itself. Thus the eros associated with the intellect (nous, logistikon) causes it to seek after truth, that associated with thumos causes it to seek after honor, and that associated with epithumetikon causes it to seek after money (or consumption). Each component in the soul, then, desires what it desires because of the respective pleasure (hdonh) afforded: the love of wisdom desires wisdom for the pleasure of learning and being wise and understanding; the love of honor desires honor for the pleasure of being honored; and the love of money desires money and consumption for the pleasure of consumption and sex. And so each type of man in whom the respective component predominates desires what he desires because of the respective pleasure involved. In Plato the Hellenic functional understanding of the human interior since Homer (and before, of course) has reached an apex; it is arrived at through a phenomenological description similar to Freud's psychoanalytic reflections that reveal id, ego, and superego as the components of the "psyche" (corresponding in some rough way to Plato's three parts of the soul), producing or suppressing the movement of the libido (corresponding to eros). Not only is the structure of the soul not revealed in its complete form in the Republic, but here the term eros is used only to refer to the motivator behind the appetitive component, creating confusion:

On the basis of this latest understanding of the human interior, Socrates provides, in total, three proofs of how the philosophic life or the "just life" is in itself preferable to the unjust or purely pleasure-oriented life; that is, why the just life is a life of greater happiness (eudaimonia) than the life of the unjust person. It is in the first proof that the eidos of justice, along with the understanding of the virtues of the soul, comes into completion.

The eidos of justice and Plato's arguments for the desirability of being just regardless of rewards The first argument: why the tyrannical man is in fact the most miserable: The first argument is a function of a re-definition (form) of justice as order. This form of justice -- recovering the primordial human experience of order from the degenerating doxa -- penetrates to the condition of possibility of a just personality. In continuity with the foregoing, the just personality on the microcosmic level is made visible via the image of its macrocosmic equivalent of the perfectly just city that is completed in the poleogony. On that side, the perfectly just city is the most orderly functioning city -- the supraorganism with the highest degree of homeostasis: This -- "the money-making, auxiliary, and guardian classes doing what's appropriate [... oikeiopragia], each of them minding its own business in a city [ekastou toutwn to autou prattontoV en polei] -- would be justice and would make the city just" (434 c 6). The formal definition of justice -- the fourth virtue -- is thus that which "provided power to [the other three virtues] so that they came into being" and which, "they having come into being, provided them with preservation as long as it's in the city" (433 b 9: o pasin ekeinoiV thn dunamin parescen wste eggenesqai, kai eggenomenoiV ge swthrian parecein, ewsper an enhi). Injustice would then be the opposite:

Polypragmosyne and oikeopragia define respectively injustice and justice. The justice of the Person, of the same form (eidos) as that of the city, consists then in the same homeostasis ("internal equilibrium", as identified earlier), harmony, or oikeopragia among the calculative part, the spirited part, and the desiring part within the soul.

Injustice within the Person then consists in a disruption of this homeostatic state maintained by oikeopragia:

Recall virtue. "Virtue" is identical with, or the post-condition of, justice. In the state of homeostasis called "justice", each component in the soul functions according to its specific "virtue", i.e. is in its maximally orderly state: the spirited part - courage (andreia), and the calculative part - wisdom (sophrosyne). The virtuous state of a just soul is in exact parallel with that of the kallipolis

Of all the components, the desiring is evidently the most problematic; it has no specific virtue, for its very function is the disruption of the order of the whole organism; it must be held in check, because it is the most major source of injustice:

When the calculative and the spirited part have succeeded in containing the rebellious desiring part, and the first rules supreme of all, the soul is "virtuous" and in the state called justice, for the work or function (ergon) of the soul is living (to zhn: 353 d 6), and a virtuous soul -- a just person in whom such hierarchy of mastery is firmly established -- lives well -- rules and manages itself (arcein kai epimeleisqai) well, and is healthy and thus happy, and an unjust soul possessed of vice lives badly and is unhappy (353 e - 354), for "virtue... would be a certain health, beauty, and good condition of a soul, and vice a sickness, ugliness and weakness" (444 e). Plato's classic argument is based on an analogy between justice and injustice in the soul and health and disease in the body: Health is defined as the establishment of an order by nature among the parts of the body; disease as a disturbance of the natural order of rule and subordination among the parts. The establishment of an order by nature in the soul in such a manner that, of the various parts of the soul, each fulfills its own function and does not interfere with the function of the other parts, is called justice... (Voegelin, p. 64)

(Adopted from Voegelin, p. 109.) The tyrannical man, or the most unjust man, is then that unhealthy, sick soul in whom the desiring (Eros in the restricted sense here: ErwV turannoV: the appetitive) is not held in check but has come to enslave and rule "what is not appropriately ruled by its kind"; hence he spends out his resource fast in order to satisfy his appetite (537 e), robs from his parents (574 b4), and otherwise wastes away his necessary relations (574 c). There is but chaos in his interior and he lives badly and cannot be said to be happy. On the macrocosmic level, this is also how unjust deeds arise in the polis (575 b6) -- through the citizens' devotion to money-making and consumption in order to satisfy the desiring part in them (their devotion to their dissipative functions). Socrates provides a vivid description in 574 e of the aftermath of a successful rebellion by the desiring part: Once a tyranny was established by eros, what he had rarely been in dreams, he became continuously while awake. He will stick at no terrible murder, or food, or deed. Rather, eros lives like a tyrant within him in all anarchy and lawlessness; and, being a monarch, will lead the man whom it controls, as though he were a city, to every kind of daring that will produce wherewithal for it and the noisy crowd around it -- one part of which bad company caused to come in from outside; the other part was from within and was set loose and freed by his own bad character. Analogy with modern psychoanalytic theory is being extended here: eros (in the restricted sense) can be identified as the id surfacing in dreams, when the intellectual part (the superego) is at its weakest. Like id, it is described as wanting intercourse indiscriminately with mother, gods, beasts, or as attempting any foul murder, as abstaining from no food (571 d). We thus enter into the demonstration that doxa's perfectly unjust man, who is supposedly the happiest because he gets to do the most injustice while getting away with it through either the acquisition of power (Thrasymachus') or deception (doxa's), in fact is the most wretched precisely because he does the most injustice: what in doxa is thought to bring the greatest good is in reality bringing the greatest harm. Doing injustice, therefore, can in the end never be more profitable than doing justice. Plato reinforces this point at the end of Book IX by means of an image of the tripartite soul, likening the intellective part to a human being within the whole association that is the larger human being, the spirited part to a lion, and the appetitive part to a "many-colored, many-headed beast that has a ring of heads of tame and savage beasts" (588 c 6: μιαν ιδέαν θερίου ποικίλου και πολυκεφάλου, ημέρων δε θηρίων έχοντος κεφαλας κύκλωι και αγρίων).

In our immediate experience (the functional perspective), the appetitive, the id, is experienced as the animal nature within us, that which we were before we became, or evolved into, human beings but which survives in us after we are fully human, a danger to be contained. The tyrant, the unjust man, is some sort of atavism. This notion of justice as the order or the internal equilibrium or homeostasis of an organism or supraorganism might seem radical as it departs from the ordinary, doxic notion of justice as honesty with others' money, not infringing on others' properties through theft and robberies, loyalty, contract-honoring, but, as hinted at, Socrates is here unearthing the underlying cause of justice and a just person: a person who has "set his own house in good order" is he who will not commit unjust acts which are the opposites of these (442 e3 - 443 a3). Once he has become "entirely one from many, moderate and harmonized", to continue from the above description (443 d) of the person in homeostasis:

Honesty with others' money, not infringing on others' properties through theft and robberies, loyalty, contract-honoring, not coveting others' spouse, etc., are all behavior which reins in the appetitive and helps produce harmony in one's interior ("justice"). There are two reasons why the person who has most set his interior in order and harmony, has most achieved homeostasis, is precisely the philosopher. Firstly, it is precisely in the philosopher that the appetite is the most subdued and the intellect the most ruling: Now since unjust actions such as robbery, theft, cheating, adultery, and murder are -- to say it again -- for the sake of satisfying the bodily desires, the philosopher is also the least inclined toward doing such injustice to others, and the most just person. This of course raises the question as to the status of the "pleasure of the soul with respect to itself" or the pleasure in learning, the problem of the eros associated with the intellective, which is covered in the second and third proof. There Plato is going to affirm the superiority of the orderly soul in this life also in terms of pleasure, by demonstrating that philosophic pleasures are better, or best. Secondly, the philosopher would be in the habit of imitating the forms (being, on) he studies and admires, "those that are in regular arrangement and are always in the same condition, neither doing injustice to one another nor suffering it from one another, but remaining all in order according to logon" (tetagmena atta kai kata tauta aei econta... out'adikounta out'adikoumena up'allhlwn, kosmwi de panta kai kata logon econta; 500 c). The study of the orderliness (politeia) in nature -- nature's conditions of possibility or its laws -- is supposed to generate in a person the same orderliness (politeia), which is precisely the order just gone through. This is especially the case within the perspective of microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism in which Plato operates. But it holds roughly true also in the differentiated perspective of today's culture: we all come to expect from our experience that those who read all the time, those who are educated, those who spent their time studying the heaven above and the nature in front and human beings and their societies and histories, those who have received the Nobel prizes in sciences, are less likely to commit murder and theft and the other things that we expect uneducated street people to commit instead. In the same vein, it is when the calculative and spirited part, through lack of training (paideia) in music, gymnastic, arithmetic, and philosophy, or in today's world, in reading, writing, mathematics, and sciences, are overtaken by the appetitive part since the person's young age that he or she commits the commonly regarded unjust acts, or finally enters politics and business and desires to become a tyrant who can command all the riches there are and enslave all the persons around. But such a person -- the type of Thrasymachus' tyrant or Glaucon's happiest unjust man (who has the reputation of being the most just) -- is because of this improper configuration of mastery and being mastered (444 d 6) precisely almost the most wretched within himself: a slave to his passion, "maddened by desires and eros" (578 a 9), as when he steals gold and enslaves his sons and daughters; to feed his insatiable desires, he desires becoming the ruler, and, if he succeeds, he will be the most wretched possible -- more wretched than when he was a mere private person -- because now he has the means to satisfy his desires without end; yet for all that he hides and can't go anywhere (579 b) because he has constantly to worry about assassination as retribution for his injustices committed along the way or because others like him covet his position; he who is most disorderly inside, in whom the philosophic-philomathic part, the most divine part (το θειότατον), is ruled by the most godless and polluted part (το αθεωτάτον και μιαρωτάτον), and who "has no pity"... he is the unhappiest and lives most unpleasantly in this way, a tragic product of lack of proper, philosophical education since young, while the most just, the philosopher, is just the opposite, being the most orderly inside, and consequently lives the most pleasant life, thanks to his education and life-long interest in things of the heaven. In ancient times tyrants abounded in positions of power, whether because the easy inheritance of such positions in dynasties, with all the temptations, liberated the appetitive eros in the new king, or because royals and commoners actively sought absolute power in order to satisfy the powerful appetite in them, such as the Macedonian Archelaus mentioned below, the many rebel war lords throughout Chinese history such as Zhang Xianzhong (張獻忠 1606 - 46) during late Ming, who enjoyed the sadistic pleasures of butchering, raping, pillaging, and digging out fetus from pregnant women, or Hong Xiuquan (洪秀全) and his associates of the Taiping Rebellion, who after securing rulership all started living a life of extreme luxury and surrounding themselves with concubines drafted from the conquered population. The history of modern nation-states still witnesses the appearance of the same figures: Mao, Saddam Hussein, Stalin, Kim Jong-Il. These all typify the portrait Plato has given of the tyrants in whom the appetitive has taken over: extravagant life-style at the expense of their subjects, massive injustices (often of genocidal scale) committed to secure the power that can guarantee it, unending demand and supply of mistresses, and yet insatiable in desires and living in constant fear of assassination, such that they become prisoners in their own secret palaces.... 8 Compare them with someone who would be the modern equivalent of the philosopher Plato has in mind, say, the Dalai Lama, with serenity and order in his interior, and judge who is happier.

There are however other types of "imbalance" within the soul than the unnatural rulership of the desiring part, i.e. other types of counter-minor salvation: subjecting the philotimon (or thumoeides) to the appetitive part, resulting in flattery (κολακεία) and illiberality (ανελευθερία), etc.; or the philosophic part to the philotimon part, resulting in stubbornness (αυθάδεια) and bad temper (δυσκολία), etc. Once again, the purpose of just actions in classical times has more to do with the preservation of the internal order of the doer than with the welfare of the others acted upon. It is for this reason that Bloom remarks rightly in the preface to his translation that "it is questionable whether Plato had a 'moral philosophy'" (p. x), and elsewhere designates the just life as the "aesthetic life". The orderly (just) soul is "beautiful and good", which are what Plato and the classical gentlemen really strive after. As the belief in the natural equilibrium of fate has disintegrated, Plato replaces it with "doing good for the sake of one's own order." Plato's exposition of the conditions of order and disorder within the human psyche in terms of the tripartite structure provides answers to two of the questions that those of a more sensitive nature ask perhaps daily. Leaving the second one for later, the first is: why is it our primordial experience that what we want naturally or in the first instance always seems to be bad or judged so by those around us? Hearkening back to the "characteristic of tradition", we recall Chris Knight's observation that the mindset, or cognitive map, of a socially active human is structured in inverse of that of an unsocial, free-roaming animal: whereas self-interest and the drive for satisfaction of desires govern that of the latter, social duties implying self-sacrifice, altruism, and repression of desires structure the former. "The communal map unique to humans is sociocentric, its motivational biases regularly inverting those of ordinary perception -- so that onerous social duties... are positively marked, while opportunities for sexual self-indulgence are marked 'danger' or 'taboo'." ("Darwinism and Collective Representations", in The Archaeology of Human Ancestry, p. 331.) We have explained this along both the material meaning of history (as the effect of the formation of the supraorganism on its constituents) and along its spiritual meaning (as the result of appreciation of order-formation in an universe thermodynamically disintegrating away). In view of the previous discussion, we can further elaborate on the materialist explanation: this effect comes about because what we want in the first instance are usually what our body wants, i.e. the desires of the appetitive in us, the satisfaction of which requires taking from others and exploiting them, thus threatening group formation and harmony. It requires training to direct one's eros from the site of the appetite toward the upper sites, until that of the intellect, whose pleasures would harm no one but "makes it easy for others", in fact. (The ascent of eros explained by Diotima in the Symposium.) Hence even a virtuous wife in patriarchal society is constituted on the model of a philosopher here.9 No wonder that "a word which used to mean the manliness of man has come to mean the chastity of woman"; this "one of the great mysteries of Western thought" (Bloom, ibid., p. xii) is thus solved: justice as the health of one's own soul has the external reflection that it does someone else good. Here lies the origin of the "traditional value" universal across human societies -- restraining one's appetite and desires is good, or is regarded by others as good -- which only modern capitalism that liberates selfishness and contemporary consumerism that elevates consumption have reversed, in order to enlarge the "market". The precedent of the first argument in the Gorgias.10 In the Gorgias a battle similar to that between Thrasymachus and his Company on the one side and Socrates-Plato on the other occurs between Polus the disciple of Gorgias and Callicles the statesman on the one side and Socrates-Plato on the other. There Polus assumes that everyone, including Socrates, must in fact envy those in power who can execute people and confiscate their property at will ("as they think fit": a dokei autwi) -- though the descriptive used for their doxic fortune is "having great power" (to mega dunasqai) rather than "happiness" -- that, in the case of Archelaus who gained rulership of Macedonia "by an impressive series of crimes" (Voegelin, ibid., p. 27), everyone would prefer being he that got away with injustice to being his victims or anyone else in that land; that, that is, the happiest (the most blessed) is he who commits injustice while escaping punishment (kolazein) or without paying penalty (dikhn didonai), and the most wretched (aqlioV) is he who suffers injustice (without, it seems, the chance to exact penalty from the wrongdoer: the counterpart of the tyrant). In fact, Callicles is to affirm that people attempt to avoid this most wretched fate of suffering injustice by acquiring power and becoming a tyrant, the happiest, who never has to suffer injustice but can commit injustice at will. We see that these are precisely the views which underlie Glaucon's proposal of the "social contract" as the origin of justice and Thrasymachus' notion of justice as "the advantage of the stronger". Here too Socrates holds, and attempts to demonstrate the correctness of, just the opposite view regarding "the order of evils" (Voegelin, ibid., p. 36), from the least to the most wretched fate: (1) to suffer injustice; (2) to commit injustice; (3) to commit injustice and get away with it. Here, without yet making use of the tripartite structure of the soul, Socrates accomplishes his demonstration through direct appeal to the primordial phenomena or human experience of the beautiful or good (kalon, agathon) as pleasant (hdea) and beneficial (wfelima), and of the bad or ugly (aiscron) as painful (luphi) and evil (kakwi). Polus is then forced to admit that doing injustice is evil and ugly though less painful, and suffering injustice less evil and ugly though more painful, by which, then, is established that doing injustice is more evil than suffering injustice. Polus has to hold to this "conventional view" (see below) because, on the surface, the "social contract" requires it. But in fact the convention comes from the primordial experience of order which is now forgotten due to differentiation but which Socrates tries to recover here -- reintegrate into the newly differentiated consciousness ("... conventions are not conventions... their truth can be confirmed through recourse to the existential experiences in which they have originated"; Voegelin, ibid., p. 32 - 3). Next, if justice is thus beautiful, good, beneficial, and pleasant -- as according to human primordial experience and convention -- then he who has done injustice and pays penalty (dike) for it suffers justice and is thus benefitted and becomes better in soul (beltiwn thn yuchn gignetai, 477) because his soul is relieved of evils (kakiaV yuchV apallattai), i.e. of the disorder caused by the indulgence of the appetite in doing injustice. Just as sickness is the evil (disorder-causing) for the body, so injustice and vice (ponhria) are harm (blaph: disorder-causing) to the soul; and just as a sick body is submitted to the doctor who causes it pain in order to restore it to health/order, so a sick soul is submitted to the law court which causes it pain (punishment) in order to restore it to health/order. The unjust and disorderly soul which escapes punishment is therefore in a less beneficial state, and hence less happy or blessed (makarion) than the one which did not. Thus it is established that doing injustice and getting away with it is a more wretched state than doing it and getting punished for it ("it is worst [the most unhappy state] to remain in the disorder of the soul which is created by doing injustice and not to experience the restoration of order through punishment"; Voegelin, ibid., p. 37). Socrates' statement in 591 a 5 - b 8 above is an elucidation of this thinking in terms of the tripartite structure of the soul. Below, Socrates' elucidation will be without recourse to the tripartite structure. At this stage Plato has not yet advanced the phenomenology of the soul in terms of its tripartite structure; the conception of the soul underlying this argument in the Gorgias is still that underlying asceticism or purification of the soul. That is, the argument here works because the "soul" (the compact experience of metabolism plus consciousness) is taken as an independently existing thing just like the body: in the immediate (primordial) experience of self-consciousness (the functional perspective) we indeed experience our conscious interior (the "I") as an object rather than as an emergent property, an effect, only, and the indulgence in bodily pleasures obtained via injustice toward others is indeed experienced as creating in that interior disorders which are experienced as either dispersion of the order of the interior -- the "disturbance of the orderly arrangement of the soul" is the image used below -- or as "thing-like" incrustation to the "interior". This is the primordial experience of order that is lost (c.f. the previous analysis of sweating as a hunter's purification). Once the experience is lost, the soul itself dwindles away and the human being is reduced to perfect identity with the body, a pure appetitive, a walking intestine with sexual organs, and the satisfaction of their needs -- ultimately via tyranny -- consequently becomes the only ingredient constitutive of happiness, so that bodily pleasures have become the only good: hedonism, the purely thermodynamic meaning of life. However, for someone who still remembers or has recovered the primordial experience of order, the bodily pleasures become rather like a curse, a disease, because now the disorders created by them -- the very eclipse of the soul through the "incrustation of dirt" -- become visible. The hierarchy of good or the order of evils is thus inverted back to its primordial form. After Polus comes Callicles to debate Socrates. His worldview is the same as Thrasymachus': the survival of the fittest, and such is just: a-morality as morality.

Callicles identifies the superior (to kreitton) and the stronger (iscuroteron) and the better (beltion) as all the same thing (488 c 8), and by these he means "those who are wise as regards the affairs of the polis, as to how properly to manage them, and not only wise but courageous [manly], being able to carry out what they intend to the full, and who will not falter through the softness of soul (oi an eiV ta thV polewV pragmata fronimoi wsin, ontina an tropon eu oikoito, kai mh monon fronimoi, alla kai andreioi, ikanoi onteV a an nohswsin epitelein, kai mh apokamnwsi dia malakian thV yuchV; 491 b). But, as Callicles fully demonstrates in his speech in 492, the wise exercises his "wisdom" and "courage" and obtains office only in order to satisfy his appetite -- this a-moral view based on the eclipse of the soul by the appetite of the body -- as if even the "best" human being were no more evolved than beasts. Again, hedonism.

Because the satisfaction of bodily desires is "natural" -- beastial -- and thus "good" and identical with "happiness".

This "true justice" of the sophist -- justice by nature (physis) -- as injustice and "true virtue" -- virtue by nature -- as vice is opposed to their false forms under "convention" (nomos). Note this important distinction the sophists have made. So Callicles explains the origins of justice and virtue: