ACADEMY & GALLERY

2007 by Lawrence C. Chin. The second argument. We see in the foregoing Platonic anthropology three types of men being identified, each naturally suited for one of the three classes in the completed polis, and who are each the type they are by virtue of their seeking the respective objects proper to them: the wisdom-loving (philosophon) seeks after wisdom and learning due to the predominance in him of logistikon, the honor-loving (philotimon, philonikon) after physical mastery, victory, recognition, and honor, due to the predominance in him of the spirited part, and the money-maker (philokerdes, chrematistikos) in whom the appetitive predominates, after money as a means to satisfying the desires of his body. These three types, moreover, so seek because of the pleasures that the respective objects they seek after provide: the pleasures of learning for the first, of recognition for the second, of the body for the third. Now, of these three types, each would claim his pleasure to be the best, i.e. the most pleasant (ηδίστη, 582). The money-maker will assert that, compared to gaining (κερδαίνειν; i.e. to the pleasures of food, drink, and sex that gaining provides in turn), the pleasure in being honored (την του τιμασθαι ηδονην) or in learning (την του μανθάνειν) is worth nothing; the lover of honor will believe the pleasure from money and the body to be a vulgar thing (φορτικήν τινα) and the pleasure from learning to be "smoke and nonsense" (καπνον και φλυαρίαν); and the lover of wisdom will consider all the other pleasures to be far behind (πόρρω) the pleasure of learning the truth as it is (του ειδέναι ταληθες όπηι έχει; 581 d 5 - e). Who is right then? What is the standard by which we can judge that only the philosopher is right in regarding his pleasure as the pleasantest? The previous argument might have established the pleasures of philosophic contemplation as superior to pleasures of the body in that the former set the human interior in order, while the latter sorts do just the opposite, so that the former lead to happiness while the latter to unhappiness. But now Plato is struggling with the problem of proving that philosophic contemplation in itself is more pleasurable than consumption or sex. There are two parts to the first of the Platonic-Socratic arguments for this. Firstly, Plato argues that the pleasure from the satisfaction of appetite, from consumption or dissipation (proper to philokerdes), is the most basic, accessible to all human beings, belonging to the lowest denominator, while the pleasure of learning (of being: tou ta onta maqanein) belongs to the "highest", latest developmental stage, only accessible to a few who have reached that stage. The philosophon would have already known what the pleasure of consumption and sex is like (and the pleasure of victory and honor as well), having passed through long ago that lowest stage (and then the intermediate stage of honor-loving) before reaching the highest developmental stage, but the philokerdes, being stuck in the lowest developmental stage, does not -- and is out of the simpleness of his mind unable to -- know what the pleasure involved in learning truth as it is (tou manqanein authn thn alhqeian oion estin) is like. Therefore the philosophon can judge best, having had experiences of all three types of pleasure (582 d: εμπειρίας μεν αρα... ενεκα κάλλιστα των ανδρων κρίνει ουτος): if he claims the pleasure of learning to be the pleasantest of all, he would be right. The honor-lover is in the middle, being right in judging the pleasure of honor and recognition to be pleasanter than that of food, drink, and sex, but, like the money-maker, unable to comprehend the pleasure of learning; while the money-maker cannot understand the pleasure of honor as well as that of learning, and is in no position to accurately assess these two types of pleasure in relation to the fulfillment of his craving for food, sex, drinks, and luxury. The second part of the first argument consists in the assertion that the instrument of judgment "is not the instrument of the lover of gain or the lover of honor but that of the lover of wisdom" (582d 8) since it is by experience (εμπειρίαι), prudence (φρονήσει), but especially by argument (logos) that the judgment as to the quality and intensity of pleasures must be made (δειν κρίνεσθαι), and these constitute precisely the means with which we philosophize. The judgment made by the philosopher -- here regarding the relative quality and intensity of different types of pleasures -- then would be "truer" as compared with the judgments made by the other two (582e 9).

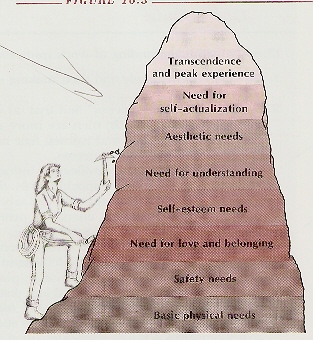

Let us seriously examine this argument (in two parts) for its validity. In regard to the first part, note that, in today's psychology, we find many instances of the same type of linear, one-way developmental scheme as Plato's for pleasures, whether it be the three psychosexual stages of Freud's, elaborated in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, and which are also concerned with the evolution of pleasure or eros; the psychosocial stages of Erik Erikson's; the humanist psychologist Abraham Maslow's "hierarchy of needs"; or Lawrence Kohlberg's moral development schema. We here single out Maslow's hierarchy for comparison because the criticism to which it has been subjected applies equally well to Plato's schema here. Maslow's hierarchy (Figure above) "ascends from simple biological needs to complex psychological motives, culminating in 'self-actualization' and 'self-transcendence'" (Carole Wade and Carol Tavris, Psychology, 1987, p. 379), which itself culminates in the "peak experience" of the mystics, as we have seen (Introduction). Plato's hierarchy operates similarly, the satisfaction of appetite being that of simple biological needs, and the desire for others' recognition of one's worth (honor) corresponding naturally to the middle segments of Maslow's hierarchy, the need for love, belonging, self-esteem, and respect, while the aesthetic needs and self-actualization respond to the contemplation on truth as it is -- and Aristotle is to explicitly articulate an identity between these two sides. The point here is that "Maslow argued that your needs must be met at each level before you can even think of the matters posed by the level above it" (ibid.). Plato's similar view is brought out in Diotima's speech in Symposium.1 Like Maslow's schema, then, Plato's second argument (the first part thereof) presupposes, firstly, that one has to pass through the lower stages of the fulfillment of bodily functions and of honorable recognition by others before reaching the highest stage of philosophic contemplation, and, secondly, that the philosopher, having experienced all types of pleasure in this way, would actually regard the pleasure from philosophic contemplation as superior to (i.e. pleasanter than), say, the pleasure from heterosexual encounters. Is this true? The experiential motivation for the two presuppositions seems to be that, relatively, so few people seem capable of understanding and practicing philosophy, such that it must be a "higher activity", and that, furthermore, philosophy is, given its difficulty, a much more precious thing to which one would prefer nothing else. But the consideration of Maslow's case might convince us otherwise. A fatal problem with Maslow's hierarchy is that "it is just as possible to organize human needs horizontally instead of vertically. One could argue that people have simultaneous needs for basic physical comfort and safety and for understanding, self-esteem, and competence... [Then,] 'higher' needs may overcome 'lower' ones. Human history is full of examples of people who would rather starve than be humiliated (a 'self-esteem' need), rather die of torture than sacrifice their convictions, rather explore, risk, or create new art than be safe and secure at home" (ibid., p. 380). Reversely, those who are "self-actualizing" could still desire greatly the satisfaction of physical needs such as for food and sex, and we can also think of examples of people who would rather give up convictions than sacrifice the opportunities for eating, drinking, and whoring. It does not seem to be the case that one can realize the higher experiences -- such as self-actualization and peak experience -- only after one has already satisfied the lower needs, such as for love and belonging, for sexual and sensual intimacy, for touching, even. In the same way, one can argue that the three types of pleasures Plato has isolated in his tripartite division of the soul are probably better organized horizontally just as Maslow's needs should be. Because of this breakdown of a linear, irreversible progression from the biological through the psychological to the intellectual needs and satisfaction, from the simple to the complex, the objective judgment as to the worthiness or quality of the pleasure in question which depends on this progression breaks down also. Indeed, today's academia is filled with "intellectuals" who have never passed through the "lower stages"; who, in fact, come to the life of the intellect as a substitute for, or as sublimation of, the "lower pleasures". The possessiveness with which many of them comport themselves toward their books -- every book read must be had, no book is to be lent out, the loss of the books had makes for occasion of the greatest fear -- makes manifest the fact that, in studying, they are infants groping after objects of satisfaction, books and knowledge being sublimated nourishment or milk of which they perhaps have not had their fill during infancy. We have considered these introverted, socially disabled "subhumans" ("The Consumerization of Mind and Culture"), who excel others of their kind, other socially disabled subhumans who today people the mental health system in advanced countries: for the subhuman kind is of two sorts, the intellectual sort in universities, and the non-intellectual sort in the mental health system. It would in fact be hypocritical for the "intellectual subhumans" to shout that they live in a greater amount of more preferable pleasure than do the rich playboys versed in the night life. They have been somewhat forced into their niche, from which they would get out if they could. Finally, a gifted philosophy major can easily be imagined to have met the love of his life at long last and lost interest in philosophy altogether. The pleasures of the body are neither necessarily "pre-requisite" to the pleasures of the intellect, nor less preferable than these. It seems that Plato has failed in the first part of his second argument; perhaps a truly happy life -- still a just life -- is not one where the higher of the pleasures excludes the lower ones, but is complemented by and organizes these others according to a certain proportion (logon), all the pleasures themselves being incommensurable one with another. We shall see later that Plato has perhaps in the end, and Aristotle has certainly in Nicomachean Ethics, come to such conclusion. In the meantime, we may offer other reasons than the quality of the pleasures themselves for which the pleasures of the intellect would be preferable to the pleasures of the body. (Other reasons than, that is, the order of the soul or interior.) We may point out that the pleasure from the satisfaction of appetites and of sexual, sensual, and romantic needs can be easily taken away -- such as when an accident or market shift suddenly deprives one of all one's wealth or when one's love suddenly takes off without a word, never to be seen again -- while the satisfaction resulting from the theoretical understanding of how the universe works stays with oneself permanently, less subject to the vicissitude of social life. This finds echo in Aristotle's later observation that intellectual satisfaction requires little or no external equipment. This is not an argument confirming that the intellectual pleasures are more pleasant than the basic pleasures, but only that they are more secure -- and preferable in this way to the latter.2 Secondly, a person can already have had enough, or so much bodily pleasures (e.g. sex), as to no longer find them pleasurable, as to no longer need them. Or, in a similar way, as Cephalus comments in the very beginning, when a man gets old and his body declines, i.e. when he is no longer capable of bodily pleasures and when the soul is automatically purified in a way, then turns he all of a sudden to the "pleasures of speech" ("pleasures of the intellect"; 329 c - d; Bloom, ibid., p. 313). In other words, when a person is young, the pleasures of the body competes powerfully with those of learning, with those of the soul. But a well-ordered man by nature is presumably a person of such type that, while growing up, or as he starts traversing through his life-cycle, he gets to satisfy all his lower, bodily, emotional, and relational needs, so that by adulthood he is ready to devote himself entirely to theoretical, philosophical contemplation, can find the greatest, or rather the most satisfying, pleasure therein, and will thus become the happiest. In other words, it seems that, if the horizontally organized pleasures are indeed traversed vertically in the right developmental order, Plato's second argument would be valid. But this shows that the pleasures of the soul (of the intellect) are longer lasting -- in addition to being more secure -- than those of the body, as they never decline in a person who loves wisdom since youth, even as he loses interests in things sexual in old age. This fact is amply demonstrated in some of the legends about famous tyrants, of whom it is said that after orgy on a daily basis with as many women as they had their eyes on and found pleasing, they eventually became numb in heterosexual matter, fell into depression because women could no longer give them the pleasures for which they live, and had had to resort to using pretty boys in order to feel pleasures again. (Such is said of Hong of Taiping Rebellion, for instance; ibid.) This is then the second aspect of intellectual pleasures that makes them preferable to the pleasures of the body. The insertion of Cephalus' speech concerning sex means that Plato must be aware of this aspect. On the other hand, the preferability of the philosophic pleasures to the somatic ones that we have thusly demonstrated, it should be kept in mind, constitutes no denial of the former admission that pleasures from the body and from sexual love in particular are not necessarily commensurable with the pleasures from contemplation and learning. One cannot study or contemplate all the time; during the "breaks", one may very well seek some "happiness" in sexual companionship or in other pleasures of consumption. On the other hand, even when one really loves the person, sometimes one wants to take a break, and be alone to contemplate on the laws of nature. We would then come back to Aristotle's later -- and possibly Plato's final -- conclusion mentioned just above, a more "humane" version of philosopher, which we will see below. Before moving on to the critique of the second part of Plato's second argument, we may mention Eric Brown's (ibid.) alternative interpretation of the first part of this argument which does not produce as Plato's underlying view a linear, hierarchical organization of pleasures from the most basic to the most developed, but rather a horizontal organization of which the philosopher takes up a greater share than do the money-maker and the honor-lover. "It has sometimes been thought that the philosopher cannot be better off in experience, for the philosopher has never lived as an adult who is fully committed to the pleasures of the money-lover. But this point does not disable Socrates' argument. The philosopher does not have exactly the experience that the money-lover has, but the philosopher has far more experience of the money-lover's pleasures than the money-lover has of the philosopher's pleasures. The comparative judgment is enough to secure Socrates' conclusion: because the philosopher is a better judge than the others, the philosopher's judgment has a better claim on the truth. So we have some reason for thinking that the activities desired by the money-lover and those desired by the honor-lover are less pleasurable than the philosopher's activities." This version is however open to the same objection as our version is, namely, that we may quite frequently encounter in today's academia "philosophers" who with their extreme introversion and social disability have never had the experience that the money-lover has had, and that even if they have they may nonetheless choose the experience of the money-lover if the occasion arises of a mutually exclusive choice between the two. We then have to come back to the same demonstration of the preferability of the intellectual pleasures not in terms of the quality of the pleasures themselves but in terms of their durability and security. The problem with the second part of the argument concerns Plato's assumption that the act of judgment (krinein) as to the quality and intensity of pleasure is an intellectual affair. Is it really true -- while it is certainly correct that wealth and gain (ploutoV, kerdeV) are not instrument with which to form judgment -- that appetite cannot judge? Does it rather fit our experience better that pleasures -- at least some of them, such as from food, drink, and sex -- are indeed sensed, or perceived, by the appetite as to their quality and intensity, while logos (or our intellect) is only consciousness and acknowledgment of the judgment thus already made? This does not as yet invalidate this second part of Plato's argument; it does point up however a possible inaccuracy in Plato's psychology. The third argument. Here Plato's Socrates points out that what ordinary people (those of opinions) judge to be pleasure and pain may not be pleasure and pain at all, such as when they are in pain (lupwntai), as in sickness, and extol as most pleasant not enjoyment but rather the absence of pain and the repose (hsucian) from it (583d 7), or when they judge the repose from, or cessation of, pleasure (or the enjoyment they are having: cairwn) to be painful (583e), even though repose itself is neither pain nor pleasure but something in the middle between the these two (583c 6). That is, unthoughtful, people have the tendency to confuse, without realizing it, the recovery from pain with true pleasure and the loss of pleasure with true pain. This can be represented diagrammatically:

The sensationless state is confused with pleasure because it is better than pain and with pain because it is worse than pleasure.

Now Plato's Socrates brings in another aspect. Pleasure in our immediate experience is the sensation of fullness, that of the body experienced as body's emptiness' (κενότης: hunger, thirst, "sexual heat") being filled up to fullness and that of the soul (we say "mind" today) as the souls' emptiness' (ignorance, imprudence: άγνοια, αφροσύνη) being filled up with knowledge (episteme). Now, the objects of knowledge, the eidoi, are "more of being", participate more in pure being (μαλλον καθαρας ουσιας μετέχειν), insofar as they are "always the same, immortal, true" (το του αει ομοίου εχόμενον και αθανάτου και αληθείας) while the objects of hunger, thirst, and sexual desires -- food, drinks, body -- are "less of being", partake less of being, insofar as they are "never the same and mortal" (το μηδέποτε ομοίου και θνητου; 585 c). In addition, the soul, in search of the pleasures proper to itself, as the eidos of life (the fourth argument for the immortality of the soul in Phaedo), is itself "more being" than is the body in search of its own pleasures. Thus:

This gives another hierarchy of pleasures:

This hierarchy would correspond with the previous one if the pleasures of the body -- the fullness of the stomach and the satiated rest from sexual intercourse -- are not pleasures at all, but merely the repose from the pain which results from lack; and if the emptiness of our mind does not cause pain -- which would strike us as manifestly true after a phenomenological examination of the common, ignorant people.3 These two points appear valid, and the first is hinted at in Gorgias where Socrates has Callicles agree that (1) want or desire (ένδειαν και επιθυμίαν, such as thirst), as lack, is painful (ανιαρον); that (2) the satisfaction (or filling: πλήρωσις) of want, such as during drinking, is pleasurable and causes one to have enjoyment (κατα το πίνειν χαίρειν); and that the conclusion results that one enjoys oneself, though in pain at the same time, when one drinks while thirsty (λυπούμενον χαίρειν άμα, όταν διψωντα πίνειν: 496 d - 497). Though there the argument is for the purpose of demonstrating that the pleasant is different from the good, the contradiction can only be resolved by the more careful phenomenological description that drinking during thirst results only in the in-progress cessation of pain, the gradual diminution of pain by the gradual filling-up of a lack. In accordance with the preceding interpretation of the "theory of forms" in the Republic, "more of being" or "partaking more in being" means "greater purity in manifesting the single eidos at issue". The eidoi of the beautiful and the good at Plato's own time, or the laws of the universe as represented in Roger Penrose's The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe (2007), "are more" and "fill more" than food or the living body lusted after in this sense, that, if they are "pleasure-causing", they are not at the same time "pain-causing". That this sense of being -- in the sense of showing -- is indeed what Plato has intended is supported by his concluding statement after his introduction of the image of the hierarchy of pleasures:

These two interpretations of the meaning of Plato's third argument do not mesh. The first result -- that the money-making, appetitive man has perhaps confused the repose from pleasure with genuine pleasure -- is not the same as the second -- that the lesser being of the objects of his desires and the consequent lesser being of his pleasures mean that his pleasures are mixed with pain. A confusion seems to reign here, such that one cannot really be sure whether Plato has given in the Republic as proofs for the desirability of justice in itself a total of four or five of them.4 Aristotle's solutions in respect to Plato's second argument (the first part) Aristotle's thinking in regard to minor salvation is for the most part identical with Plato's, but with some elaboration. Minor salvation in Aristotle's ethics (Nicomachean Ethics)5 is identified, just as in Plato's thinking, as "happiness" (ευδαιμονία), and it consists, elaboration aside, essentially in the same thing as with Plato. Happiness Aristotle identifies as the one thing in life pursued as an end in itself (to kaq'auto diwkton) rather than something which is pursued as a means to something else (to di'eteron diwkton; I vii 4 - 5).

Plato's identification of justice (of the soul) with (the greatest) happiness and with philosophic contemplation is accepted by Aristotle -- and by most philosophers in the world until the onset of modernity -- but the latter specifically takes into account the fact of the soul's embodiment which makes its happiness ultimately and necessarily a composite of more than pure contemplation but of a moderate amount of all things, which fact therefore brings in the problem of instrumentality. That is, in answering the question, "How to be happy?", Aristotle recognizes that the above self-sufficiency or autarky of happiness does not mean a life of isolation (bion monwthn) but a life with friends, spouse, children, parents, and fellow citizens, since "human" -- that is, the embodied soul -- "is by nature a social being" (φύσει πολιτίκον ο ανθρωπος; I vii 6 - 7). We will return to the problem of instrumentality after considering Aristotle's elaboration of the eidos of virtue and his view regarding philosophic contemplation. Aristotle's conception of virtue (arete) is also the same as Plato's (or the "Greek" generally), but he expresses it differently. Aristotle defines happiness as, or as caused by, the active exercise of our natural faculties in conformity with virtue (κύριαι δ'εισιν αι κατ'αρετην ενέργειαι της εύδαιμονίας; I x 9). His conception of human being is rather like the Romantics', as "blossoming", that each individual is born as a seed with a unique design imprinted within that must be allowed to unfold through one's life course; if the person unfolds his or her potential to the maximal degree, then happiness results. And our "potential" breaks down to two kinds: doing and contemplating (πραξις, θεωρήσις). We have hence two types of virtues (virtues as the maximal expression of our potential and so as our means to happiness): the intellectual (τας διανοητικας) and moral (τας ηθικας) in conformity with Aristotle's own version of the tripartite structure of the soul(-and-body). "Virtue", the excellence or maximal functioning of something, here in the moral domain takes on the explicit qualification of the famous rule of the Golden Mean: neither excessive, nor deficient, exercise of our functions. This is how he clarifies and complements Plato's discussion. Just as physical strength is destroyed by either too much or too little exercise of our body, and health by either too much or too little food and drinks, so virtues in the moral domain -- leading to happiness -- are found, e.g. in the case of courage, by neither shunning and fearing everything on the one extreme (cowardice) nor being completely unafraid of anything on the other (foolhardiness), or, in the case of moderation, by neither indulging in every possible pleasure on the one extreme (incontinence) nor turning one's back on every pleasure on the other (asceticism is not endorsed!). In other words, whereas badness either falls short of or exceeds the right measure, virtue discovers the mean. But virtue is a maximum in terms of best functioning. (Note that for Aristotle a gentleman, kaloskagathos, is he who neither becomes excessively angry at the sight of injustice nor is not angered by it at all: a person should have a moderate amount of moral indignation.)

The correspondence between Plato's and Aristotle's anthropological tripartite structure The virtues Aristotle identifies are: ελευθεριότητα "liberality"; σωφροσυνην "temperance" or "moderation"; σοφίαν "wisdom"; σύνεσιν "intelligence"; φρόνησιν "prudence", or practical wisdom as opposed to speculative, theoretical wisdom. We thus see that in Aristotle's "tripartite structure" of human being (not just of the soul), the rational part (logon) consists of two sub-divisions: "one whereby we contemplate those things whose first principles are invariable." (εν μεν ωι θεωρουμεν τα τοιαυτα των οντων οσων αι αρχαι μη ενδέχονται αλλως εχειν; VI i 5.) This is episteme (VI iv 3) and its virtue is of the theoretical type (theoretike dianoia). The other is that "whereby we contemplate those things which admit of variation (εν δε ωι τα ενδεχόμενα; VI i 5). This is either doing, practical intelligence in prudence (pratike, phronesis), or making (poiesis), such as art (techne). Since Aristotle considers human goodness to be only virtues of the soul, happiness can only be the exercises of logon and alogon in accordance with their respective virtues (epithymetikon exercised to the maximal in respect to functioning, for instance, i.e. in moderation in respect to quantity, results in "liberality"); the exercise of bodily functions doesn't even figure into happiness (αρετην δε λέγομεν ανθρωπινην ου την του σώματος αλλα την της ψυχης. και την ευδαιμονία δε ψυχης ενέργειαν λέγομεν; I xiii 6). This merely continues Plato's scheme of things, where epithymetikon (there referring to the appetitive) has no virtue of its own. Happiness of the alogon consists in moral virtues; but moral virtues, and so happiness, require external equipment (I viii, 15 - 7), whereas happiness of logon does not (X vii, 4). To embody "liberality", for instance, one needs friends with whom to be so, political office or power with which to impart favors to others, or wealth to lend to others. At the very least, the just person needs the presence of other people toward whom he or she shall act justly. But the philosopher can contemplate on truth even when all by himself. We can see that Aristotle is far more perceptive than Plato in seeing the context over which a person has no control but which is either necessary for or conducive to his or her happiness. Aristotle even notes that a person with unattractive appearance or of ill-birth is less likely to be happy. Toward the end Aristotle also considers the contemplative life to be the "happiest" because (1) it is the highest human development such that the contemplative philosopher is, virtuously, exercising his or her naturally given talents, or unfolding his or her naturally given blue print, to the fullest (X vii, 1; this is almost the same as Plato's second argument, but not exactly); and (2) because it is self-sufficient (autarkes); whereas the life of moral virtues is happiness only to a secondary degree (δευτέρως: X viii 1). Now it seems that Aristotle, in regarding again the pleasure in contemplation as the highest, has lost his better insight in comparison with Plato's, but he seems immediately to have fixed the Platonic flaw by adding, firstly: "those things are actually valuable and pleasant which appear so to the good [i.e. orderly in soul] man" (X vi 5: και τίμια και ηδέα εστι τα τωι σπουδαίωι τοιαύτα οντα). The tyrannic man's judgment doesn't count. This must mean that true happiness and true pleasures are those that contribute to the order of the soul rather than those dissipating its order (as in amusement). In this way, when the philosopher and the tyrant each judge their respective pleasures to be superior to the other, the philosopher would be right and the tyrant wrong because the philosopher is the spoudaios with an orderly soul whose judgment -- always in relation to the order of his soul -- counts! This kind of thinking presupposes that order is the supreme good, i.e. the teleological point. We will return to this below. However much Aristotle might agree with Plato that the lone contemplating philosopher represents the highest developed human, the fullest actualization of human potential, he still admits: "But the philosopher being a human being will also need external well-being. For [human] nature is not sufficient toward contemplation [theorein]; he must also have bodily health, food, and other requirements [therapeian]." (δεήσει δε και της εκτος ευημερίας ανθρώπωι οντι. ου γαρ αυταρκης η φυσις προς το θεωρειν, αλλα δει και το σωμα υγιαίνειν και τροφην και την λοιπην θεραπείαν υπάρχειν. X viii, 9.) Those other therapeian presumably include the satisfaction of romantic and sexual needs and the need for friendship (philia). This is Aristotle's second conclusion. The greatest happiness is a composite: not just the pleasure of philosophic and scientific learning, but also the health of the body and a moderate satisfaction of its (and psychological) needs to the extent that it be beneficial to and maintain bodily (and psychological) health. Not the complete denial of bodily needs, not asceticism, though not a luxurious life either. The philosopher, in being human, in being embodied, should have, if he is to be happy, a moderate amount of everything a human being usually needs and wants, for his body as well as for his soul ("mind"). Now, this second conclusion of Aristotle's converges with the earlier admission of the incommensurability of pleasures. This constitutes an important modification of the conclusion of the first argument as well. In his image of the "just person" as the happy philosopher, in his image of the liberated prisoner who has gone out of the cave to dwell blissfully in sunlight, in the light of Agathon, in truth, Plato seems to give the impression that the happiest possible man is he who has seen the Agathon and let his interior be ordered by it and stays in this wise, alone by himself, outside the cave (outside society), without any need for the shadows inside the cave (things from society, the worldly things that are mere illusions). Within the framework of our "religious" interpretation of Plato, this would mean that Plato thinks that asceticism of the most severe sort, practiced for the sake of major salvation, would in and by itself constitute the greatest possible happiness -- minor salvation flowing directly from major salvation. Now, with Aristotle, it seems that this is not so. Truth alone does not provide happiness in its fullest, but only in combination with illusions. Asceticism is clearly denied by Aristotle as the path toward happiness when he posits the Golden Mean in the matter of the pursuit of moral virtues for happiness' sake. This is however not a denial of the conclusion of the first argument that the tyrant, an exemplary slave to the desires of his body, is the most wretched. For all the power he has acquired as means for feeding the insatiable beast or filling the leaky jar in him, he yet lacks some essential of the external instrument that we have now acknowledged in the philosopher's case is required for his blossoming in happiness: i.e. friendship. Aristotle has defined friendship as consisting of three types, constituted by either the mutual providing of pleasure or of utility, or by the genuine mutual appreciation of virtues (and so justice) in the other. Friendship based on the mutual recognition of virtue is the most genuine friendship -- friendship to the fullest. Only this type of friendship involves the persons in their whole being, the other two being rather incidental, and it consists in an altruistic wish for the friend to live and exist for his or her own sake. ("This person is a precious being, magnificent order-formation against the arrow of time," to speak in our thermodynamic framework of interpretation.) The tyrant, as the description goes in the end of Book VIII and the beginning of Book IX, kills, purges, and besides that, knows only to exploit and use others and then to quickly abandon them once he has exhausted their usefulness or the pleasures they can provide. He seeks only utilities and pleasures in others, but never virtues, because he does not understand these. Only a virtuous person can recognize another virtuous person. "Therefore [the tyrants] live their whole life without ever being friends of anyone, always one man's master or another's slave. The tyrannic nature never has a taste of freedom or true friendship" (Republic, 576 a 2: εν παντι άρα τωι βιώι ζωσι φίλοι μεν ουδέποτε ουδενί, αει δέ του δεσπόζοντες η δουλεύοντες άλλωι, ελευθερίας δε και φιλίας αληθους τυραννικη φύσις αει άγευστος). Has Plato come as well to the conclusion that the happiest philosopher is not an ascetic but pursues all pleasures in moderation? There are hints that Plato would agree with the realistic, "humane" portrayal of the philosopher which Aristotle has given as truly the happiest person, a contemplator who nevertheless allows the philokerdes and the philotimon in his interior to pursue in moderate amount the pleasure of gain and consumption (and of romance and sexuality, presumably) and the pleasure of being honored and recognized -- and becomes happy, because he has so allowed under the guidance of knowledge and argument (τηι επιστήμηι και λογωι) which carefully prescribe the moderate amount. This is perhaps the meaning of the mysterious Socratic concluding statement that appears immediately after "all the proofs" for the philosophic pleasures' superior pleasantness have been presented:

The happiest -- s/he who has attained true minor salvation and is the most just -- is this person in whose soul the philomathes rules even while carefully allowing the other two, lower components to pursue their respective pleasures. This is not the picture of an ascetic as seen in Phaedo. By the standard of this final conclusion, the tyrant is compared for the last time with his extreme opposite, the philosopher, in respect to the amount of pleasures and the extent of happiness in their respective lives. Earlier, after having constructed the paradigm of justice in a person, Socrates was ready to present the four forms of badness that are supposed to embody injustice in increasing degrees; but he did not have the chance to do so until after the presentation of the material that constitutes the metaphysical core of the Republic. Calling the kallipolis aristocratic, Socrates produced the four famous forms of badness on the supraorganismic scale, in order of increasing distance from the first, perfect embodiment of justice or order: timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny; and calling "aristocratic" the person whose embodiment of justice had served as the model for the demonstration of true happiness in the first argument, he gave the four famous forms of badness on the scale of Person, in order of increasing falling-short of the first: the timocratic man, the oligarchic, the democratic (which Bloom translates as "man of the people"), and the tyrannic, these being the microcosmic versions of -- and each the dominant type of person in -- the former four "bad" regimes respectively. (Remember that the polis is the soul dominant in it written large.) No longer the three types of man, but the five types of man, are to constitute the overall context -- the system of anthropological classification -- in which the final comparison can be attempted. The tyrant now appears the most distant from "true pleasure," "a pleasure that is true and properly his own" while the king-aristocrat, the closest (πλειστον δη οιμαι αληθους ηδονης και οικείας ο τυραννος αφεστηξει, ο δε ολίγιστον; 587 b5). In fact, the king-aristocrat, who resembles the philosopher the most, lives 729 times more pleasantly than the tyrant! (587 e3; more on this below.)6 This whole problematic -- whether and how much the satisfaction of bodily desires, along with an emotional life (e.g. the need for human relationship), should factor into the constitution of human happiness, even that of the "highest developed": the failure of the means for major salvation in constituting the greatest possible happiness -- has its origin in the embodiment of the soul. This is why "true", uncomplicated happiness of the soul (its happiness without the involvement of external equipment) is not possible in this life, not until the soul separates from the body upon death and dwells in the realm of the forms (if it has practiced philosophy well during life, of course). This point constitutes the essence of Cephalus' speech from 328d - 329d of which mention was made earlier: the interference of the body in the life of the soul, its demand on the soul, is so great that the soul itself might be hindered in its pursuit of happiness were it to neglect completely the bodily demand. Only the intellective (calculative) component is intrinsic to the soul; the other two arise from its association with a body and society. This problem which the embodiment of the soul causes its happiness is also what engenders the political problem of the best city. The simple polis that is easily constructed during the first stage of poleogony -- this "city of necessity" -- is in fact the best polis and equivalent to a disembodied soul. It is principally the desires of the body which cause the citizens to want riches (noosphere consumption), such that the polis has to complexify in its division of labor... And the city in regard to its political form (politeia) therewith acquires a life-cycle also, a temporal dimension -- the devolution or degeneration of the regimes described in Book IX (see below), for the city of necessity can never degenerate -- it is stable for all time because it in its simplicity is already "at the bottommost". We may at this last juncture, at the end of our exposition of Plato's arguments for the desirability of justice even under the condition of un-notice by gods and humans alike, take up the second of the mystery questions in daily life mentioned earlier: that is the question of the meaning of life. We have postponed the question till now so as to be able to answer it wholly without residue of qualification. The meaning or purpose of life in accordance with the foregoing Platonic viewpoint would be as R. E. Allen has noted: "the purpose [function, excellence, arete...] of life is to live... But if to live, then to live well, then to live courageously and wisely and temperately and justly", i.e. the meaning of life is to live "virtuously" (ibid., p. xxvi), that is, "orderly". The purpose of life is the maximization of life. But this acquires a further dimension with Plato's second and third argument that counter hedonism of the day which destroys order with a philosophic hedonism that is conducive to the right order of the soul: the purpose of life is also to live pleasurably -- "pleasure" referring here to its higher form, the pleasure of "forms", or of the laws of the universe in the contemporary world. (Contrast this answer with Ch'an Buddhism's and then with Neoconfucians' view on the matter.) This means that Plato's justice is in fact teleological and a form of hedonism above the doxic level: justice -- the order of the soul -- engenders a higher form of pleasure -- of learning and living well. Aristotle would certainly agree with this. Modern utilitarianism -- "the greatest good for the greatest number", "version of the second commandment in the order of the Mass, that thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself" (Allen, p. xxv) -- of which Mill and Bentham are the pioneering proponents may be teleological like Plato's "hedonism", but the pleasures that are regarded as "good" in this moral theory are only doxic (bodily) pleasures; hence to achieve the appearance of justice, the proponents have had to define "good" by taking into account others' pleasures. This is tied up with the previously mentioned questionable status of Plato's "moral philosophy". Plato's advocation of justice is teleological in both that "justice" as embodied by the philosophic life engenders a superior (more pleasant) form of pleasure and that it refers to a homeostatic state of living that leads to true happiness. Modern ethics (in the Anglophone world), on the other hand, has had difficulty in finding an objective basis on which to ground moral values because the teleological goods which the theorists find -- pleasures or fairness or whatever -- are dissociated from order, with which traditional "morals" form an integral. (Consider how Brown misses the point of the first argument.) Order is the condition of existence, of life, in a universe destined to "run down". That existence or living does itself according to itself (its condition) is a purpose internal to existence or living itself, as Allen has commented (ibid.). In this way the question concerning the objective status of values becomes non-applicable. But (true) pleasures and happiness as provided by the philosophic life is not the same as "good" (Plato emphasizes this in the Gorgias), but are "good" only insofar as the form of order -- politeia -- of which they are consequences is conditioned by the form of the Good: "The Dikaiosyne which imposes right order on the forces within the soul has its origin outside the soul" (Voegelin, ibid., p. 111). Order -- and the happiness that it engenders and the pleasures that accompany the activities constitutive of it -- is good because it participates in the idea of the Agathon. Once again we see at work in the Republic the same teleological view of the universe as that given explicitly in the Phaedo: the politeia -- the right relationship among the tripartite components -- is such because the cosmos is "designed" so to speak to be such. This is why politeia is identified as the natural, healthy state either of the soul or of the polis and is said to be a pattern (paradeigma) laid out "in heaven" (en ouranwi; 592 b 2). The point of the Republic: We should be just both for the sake of happiness in this life and for the sake of the happiness of the soul afterlife If justice is the greatest good -- aside from the Good itself -- then it is, as noted, both desirable in itself and for its consequences or rewards. Hence after providing three arguments demonstrating that being just is desirable in itself -- because it entails minor salvation -- Socrates in Book X returns to the "conventional way" of motivating us toward justice, motivating in view of the rewards extrinsic to it (Bloom, ibid., p. 434). The rewards are of two kinds, those in this life -- denying that being and seeming must always and even in the long run be inverse of one another, Socrates affirms that most of the time and in time the just person will reap good reputation and other good fruits from his fellow human beings as well as from gods (612 d - 613 c) -- and those in the afterlife especially, i.e. major salvation. Here Socrates first provides another argument for the immortality of the soul: for everything there is an evil correlative which can destroy it to the point of non-being (eiV to mh einai): rot for wood, rust for iron and bronze, and disease for the body. For the soul, the evil correlative, the sickness or unhealth peculiar to it, as seen, is injustice or vice. But since the injustice of the soul does not cause it to "not-be", it must be immortal. "No soul has ever died from vice, as a body has been destroyed by disease. Hence, there is no reason to assume that external events, such as the destruction of the body, will ever destroy the soul" (Voegelin, p. 130; Bloom in his Straussian approach is wrong in assuming that the Socratic argument for the immortality of the soul is not serious; ibid., p. 435). Again, the argument would work only if the underlying way of dividing up the world, the "categories" of the underlying worldview, were true or real -- if the "life" (metabolism-plus-consciousness) in a person were indeed an independently existing "thing" and not the emergent property of some underlying interactional network (of neurons and proteins). The ultimate reward for practicing justice consists therefore in this that the soul will separate from the body after death pure of disorderly configuration, of distortion, pollution, "dirt" -- "those which, because it feasts on earth, have grown around it in a wild, earthy, and rocky profusion as a result of those feast that are called happy [ευδαιμόνων λεγομένων, i.e. pleasures of the body]" (612 a) -- so as to enjoy a blissful, purely eidetic existence. The soul has then recovered its divine nature from its distortion through its community with the body. And a clue to that true nature, covered as it were by the barnacles, and crushed by the waves, of existence, is given through the soul's love of wisdom (philosophia), which is the yearning for its true company, the eternal. When in this life the soul strives for justice for its own sake, it follows that gleam of immortality toward a more perfect order, after the obstacles of bodily existence are removed (611 d - 612 a). (Voegelin, ibid.) The image of the soul now reverts from the relational back to the substantive. In parallel with the myth of the afterlife and the myth of the judgment of the dead at the end of Phaedo and Gorgias, the myth of Er or the Pamphylian myth is then given at the end of Book X to symbolize -- to provide a pictorial metaphor of -- the condition that the fate of the soul after life depends on what it does to itself via its body in this life. And also like the final myth in Phaedo, the myth of Er attempts in earnest to produce a pictorial construction of the structure of the cosmos. Thus this myth, just like that in Phaedo, is on the one hand metaphorical only but on the other a sort of scientific construct of the Presocratic type that is meant to represent as closely as possible reality, or the actual cosmos, as it is. "Er found rewards and punishments for just and unjust souls; but, more important, he also found an order of the universe which makes this world intelligible and provides a ground for the contemplative life. At the source of all things, Er saw that soul is the first principle of the cosmic order..." (Bloom, ibid., p. 427). The soul is the connecting joint between the therapy of the soul in this life through philosophy and justice and the way in which the cosmos is and functions. In both Gorgias and Republic the final myth tells of the terrible tortures which the unjust souls -- among whom the historical tyrants filled the ranks -- were made by gods to undergo in the nether portion of the after-world as punishment for their past injustices and/or in order to be cured of these -- and many, especially the tyrants', stayed in that realm for eternity, the disfigurement they had wrought on their soul through a life of vices being incurable -- and of the blissful stay in realm of immense beauty which the just souls -- such as "a philosopher's who had minded his own business and not been multi-practicing in his life" (φιλοσόφου τα αυτου πράξαντος και ου πολυπραγμονήσαντος εν τωι βίωι), as told in the Gorgias (526 c 4) -- were propelled by the order of gods to experience as rewards for their past justice. Again, given his notion of the soul as an independently existing entity with an order of its own, we must assume that Plato believed that something of such nature was true of the "after-life" and therefore devised myths not as lies but as metaphorical didactics motivating people toward justice and away from injustice. The final myth in the Republic, like what is professed in the Phaedo, but unlike the final myth in the Gorgias, also tells of the coming reincarnation of the souls after their completion of a thousand year of torment as punishment or a thousand year of bliss as reward. But in difference from the Phaedo, here the type of the next life is not determined automatically in accordance with the soul's justice or injustice in the previous life, but comes as a result of its free choice of daemons -- each entailing one particular kind of life -- thrown on the plain by Lachesis (Ananke's daughter) for it to pick. This results in complications unseen in the Phaedo, such that "[t]hose who formerly have led a dubious life, and as a consequence not only have suffered punishment themselves but also seen the suffering of others, generally are cautious"; but that "[t]hose who previously have lived a good life in a well-ordered polis, and participated in Arete from habit rather than from love of wisdom... are apt to make foolish choices. They will jump, for instance, at a glittering tyranny and discover too late the evil of the soul in it..." (Voegelin, p. 56). But -- only in this is the myth here in much accord with that in the Phaedo -- those who had found a philosopher as teacher and had properly philosophized would have learned to distinguish truly the good and the bad life, and choose a truly happy life. An additional element added in the myth in the Republic which was not found in the myth in the Phaedo is therefore the point of decision between the past and the future life, the lesson that "[t]he freedom of the present is not of much use unless the Arete of wisdom has been honored so that a right decision can be made, honoring it still more in the future" (Voegelin, p. 57 - 8). Now in regard to the structure of the cosmos in the final myth of the Republic which Er saw when he had reached its extremes, this seems to have been an elaborated version of that found in Parmenides' cosmogony. The myth, like those in the previous dialogues, clearly demonstrates that Plato has not broken through the compactness of the cosmological mode: it attempts to integrate the fate of human beings into the grand structure of the cosmos itself (microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism); the column of light with the spindle of Necessity (AnagkhV atrakton) by which the revolutions of the heavens turn recapitulates the axis mundi of the spatiality of mythic consciousness; and the souls' drinking from the water of Carelessness (Amelhta) in the plain of Forgetfulness (Lethe) before their reincarnation in order to forget the past life is also a universal element among the mythologies of the world. What Plato is doing, here as well as in others of his dialogues, is reintegrating the older myth of the cosmological mode -- whose place in the history of order has come to naught, it being destroyed "by reason and pleonexy" (Voegelin, p. 43) as we have seen, and as we shall see further -- into the new, more differentiated cosmological mode. The message of the traditional myth -- telling of karma, usually just like the Platonic one here or in the Gorgias -- was not wrong, Plato thinks, but its expression unseemly.

By way of concluding Plato's discourse on salvation and justice in the Republic, we might comment a bit on their contemporary relevance. We should not expect that Plato's discourse about justice's being the health of the soul -- or the health value of asceticism, i.e. the first argument -- might still hold perfectly today. We certainly do not believe in the immortality of this soul, its afterlife bliss assured by justice and philosophia, and its consequent fair or wretched reincarnation. In our endeavor to repeat past enlightenment of the functional perspective within our structural perspective, we must carefully distinguish what is repeatable and what is not. In our differentiated, structural perspective, metabolism and consciousness are not together constituting a "soul", but are only separate effects of physiology and neurology. A periodic and moderate amount of indulgence in sexual pleasures, for instance, disclosed today as physiological exercise of the body, is actually considered by contemporary physicians to contribute to health, relaxing the mind after intense study and helping its concentration afterwards, instead of being imagined as the trapping and damaging of a immaterial (originally "airy") soul by something of a material nature, such as Plato or the Yoga masters of past Hinduism who fast and meditate to the point of emaciation (i.e. asceticism) think! Consciousness has differentiated and enlarged its horizon since Plato, and his truth is not necessarily -- nor capable of being -- our truth. We might do well by heeding to Oswald Spengler's warning:

The Platonic doctrine of the soul lived back then for a time but is dead today -- this is why a Straussian like Alan Bloom has had difficulty in accepting that even Plato-Socrates once believed in it. Although Spengler speaks from a view of independently traversed life-cycles of cultures -- and every discourse being no more than the expression of the inner spirit of this culture at a particular point of this traverse: the objectivity of the object of the discourse not admitted -- which we do not accept, although we adopt Voegelin's view of a differentiating consciousness's gradual approximation to truth which does have objective existence, although, finally, we have a notion of history as a linear thread twisted into spirals or with overlaps, Spengler's observation holds along the way of consciousness' differentiation and below the threshold of repetitions or overlaps in the spirals. Philosophy's conflict with poetry Plato's wish since early on has been, in the words of Voegelin, "the spiritual regeneration of Hellas through the Idea [i.e. the forms]", especially via the education of the younger generation, the formation of their souls into right order (politeia). It is for this sake that the true meaning -- or eidos -- of justice is demonstrated as, in our religiously oriented terminology, "minor salvation". This shall lead our thought into two directions: first, Plato's attack on poetry, and second, the use of the salvational state for worldly purposes ("immanentization"). Hellas degenerates because of the downward movement of the great differentiation of consciousness occurring during the Axial Age, which has either corrupted traditional devices into instrument of degeneration and or created new ones. In the Gorgias, Plato attacks rhetoric as a newly created instrument for corruption. In the Republic it is poetry which Plato attacks as the corrupted instrument. In the domain of therapy for the disorder (in soul and in society) generated, the newly differentiated philosophy thus contests with poetry, which is the old device for the formation of the order of the soul, for forming orderly persons that are of use to the polis ("great is the contest concerning becoming useful or bad": megaV... o agwn... to crhston h kakon genesqai; 608 b5). The downward movement of the differentiation of consciousness is destroying the meaning of traditional myth, transmitted via poetry, so much so that Plato takes for granted that the stories (muthoi) Hesiod and Homer tell are false or lies (pseudes; 377 d 5); while the upward movement has produced philosophic enlightenment as the new mechanism for forming orderly persons appropriate to the new level of development of the collective consciousness. "What is at stake in the conflict is neither the excellence of Homer as a poet, nor even the language of the myth, so brilliantly used by Plato himself [in his attempt to re-integrate the old form into the new consciousness], but the order of the soul" (Voegelin, ibid., p. 101). In the Republic the attack on poetry -- the pointing-out of its corrupting effects in the new age of consciousness -- is conducted in two places, in Book II - III and in Book X. Overall, the problem of poetry is of two-fold: On the one hand, the language of the myth becomes unseemly (Xenophanes) when the order of existence can be expressed more truly in the language of the philosopher's soul and its experience of transcendent divinity. On the other hand, the language of the myth becomes opaque when it passes through the minds of enlightened fundamentalists. When the myth is no longer experienced as the imaginative symbolization of divine forces, but as a realistic collection of dirty stories about the gods [this is because the compact order expressed by the anthropomorphic behavior of gods can no longer make sense within the new, more differentiated, order or nomos], the educational influence even of Homer can become disastrous... (ibid.). The corrective in regard to the second aspect of the problem takes up the form of a reform of poetry in the context of the discursive construction of the kallipolis, when Plato considers the educational value of this traditional instrument along with that of gymnastic and music. There Socrates, like Xenophanes before him, proposes the purification of the eidos of god in two ways, firstly, that, contrary to the unseemly or "mixed" representation of gods in mythic poetry (e.g. that Zeus is the cause of good and evil at the same time [379 d] or that Zeus and Themis are responsible for strife and contention among the gods), "god" should be the cause of only good things, and should only be good, and, secondly, that "god" should never change forms nor lie nor deceive (378 - 383). We note that, in the first mode also, much of the changes from polytheism to monotheism involves the same operation of "making the concepts embedded in old myths logically consistent" so as to eliminate unseemliness, hence Philo, the theological debate over the problem of evil (theodicy), and so on. Then Socrates proposes the elimination from mythic poetry of all that causes fear of death (such as the dreadful description of Hades) and incites emotions, insolence, and desires (such as the description of heroes' and gods' lamentation and grief or being in want of drink and meat; 386 - 391). These are not conducive to the formation of virtues and order in the soul of the young. The attack on poetry and especially Homer in Book X is geared toward the first aspect of the problem, the unsuitability of "mimetic poetry" for the experience Plato is seeking to express artistically. Here the context is rather the banishment of poetry from the kallipolis altogether. The "theory of forms" is made use of in the clarification of the problem. An eidos, such as of a couch, shows itself in three ways, either as one form by itself, in many couches of actual use, or in many images of the couch in actual use seen in arts such as in paintings. These roughly correspond to the upper portion of the divided line (ousia), the upper portion of the lower portion (horaton), and the lower portion of the lower portion (doxaston), respectively. Its existence (or showing) as one form is its existence in nature via the production of god (η εν τηι φύσει ουσα η... θεον εργάσασθαι; 597 b 5).7 Then it exists (shows itself) as many via the production of the craftsman who makes couches for those who wish to make use of it. Finally it exists in the painting via the artist's imitation of what the craftsman produces. There are thus three types of producers in order of decreasing understanding of the being of the thing in question (i.e. couch): its "nature-begetter" (futourgon, i.e. god) who understands best what "the couch" is; the craftsman (dhmiourgon) who knows enough of the couch to manufacture it (and those who wish to make use of it, crhsomenhn [601 d], belong also to this second level and know more of it than the craftsman -- now opposed to them as the maker, poihsousan -- though less than god in their understanding of the goodness and badness of the object when it comes to its use); and the imitator (mimhthn) who knows least about "the couch" because in his representation of the object as produced by the craftsman -- not as it exists in nature, by the hand of god -- he depicts only its appearance from one particular angle, not the total object seen from all angles: the imitation in arts of the object crafted is not even imitation of being as it is (προς το όν ως έχει) but only of its looking as it looks (προς το φαινόμενον, ως φαίνεται), not of truth (αληθείας) but only of looks (φαντάσματος) (598 b). The artist as the imitator and his works are at third remove from being (τριττα απέχοντα του όντος) just as the craftsman (and the user) and his works are at second remove. The poets -- and first among them, Homer -- figure among these artists at third remove since their depiction of the "virtues" of heroes is one grade below the "using" or "making" of virtues (by the heroes themselves and by the educators) which in its turn is one grade below the eidoi of virtues as they exist in nature. The first manner in which philosophy supersedes poetry as instrument of paideia is therefore its grasp of truth as it is -- a realm of being disclosed since the poets and which was undifferentiated and hidden formerly during the age of myth, epics, and poetry. To the differentiation of this realm on the objective side corresponds on the subjective side the differentiation in the soul of the logistikon which now, in the current "relational" model of the soul, is what imposes the right order therein. The second manner in which poetry has become unsuitable for the new age is another aspect of the same problem. Here the harmful effect of the emotional appeal of epic poetry on the order of the soul which has figured as the second target of the reform of poetry is elaborated upon. As mimetic representation fine art (such as painting) is illusionism; its representation of something can pose itself from afar as the real thing to the viewer by suppressing the logistikon in the latter. Poetry works in the same way as it is primarily concerned with representation of the emotions of heroes so as to please the public who are less interested in the emotionlessness that results from the rule of the logistikon than in passions and colorful characters that issue forth from the rule of the spirited and the appetitive part. In two ways then is poetry harmful to the order of the soul by suppressing the calculative therein and encouraging the lower pleasures and emotions of epithymetikon and the thymon to rulership in the soul, leading to injustice and vice (606 d). The good order of the soul, its politeia, must be established and continuously preserved through right Paideia (608 a - b). If the soul is regularly nourished by influences that play on its passions, the strength of the rational element, the logistikon, will be dissolved (605 b) and with it the faculty of measuring rightly (603 a); instead of the good a vicious (kake) politeia will be set up in the soul (605 b). In the surrounding society, the principal source of the vitiating Paideia is mimetic poetry, represented by Homer and Hesiod, by tragedy and comedy. Bloom elaborates on poetry's repression of the logistikon in terms of the suppression of any attempt to liberate oneself from convention -- from the shadows on the wall in the cave. Since the right order of the soul is established through the embodiment of the Agathon whose vision comes only through the faculty of the calculative, the falling-short of the right order means also the failure to extricate oneself from convention -- the sophistic society. The poet "must appeal to an audience [i.e. the public, the prisoners in the cave]; and in that sense he imitates the tastes and passions of that audience. But the tastes and passions of the audience have been formed by the legislator, who is understood to be the craftsman who builds the city according to the pattern provided by his view of nature. Thus the poet, who looks to the audience which looks to the legislator, is at the third remove from nature" (Bloom, ibid., p. 432). This means that the poet reinforces the public's attachment to a convention that is merely shadows of nature -- the prisoners' attachment to the shadows on the wall in the cave -- and their distance from the right order of the soul.8 The "virtuous hero" such as Achilles which the poet glorifies to the public is not virtuous at all, but merely a man given to passions (p., 359). The flip side of all this is that "the poet is unable to imitate the best kind of man, the philosopher" (p. 359 - 360) which only the symbolic form of the dialogue succeeds in representing. Summing up the foregoing, we can put Plato's conflict with poetry in the historical context (in the history of order). Voegelin (p. 133): The attack on Homer, in order to be intelligible, must be understood in the context of the "old quarrel" (palaia diaphora) between philosophy and poetry in which it is placed by Plato (607 b). The discoverer of the psyche and its order is at war against the disorder, of which the traditional education through the poets is an important causal factor. The philosopher's Paideia struggles for the soul of man against the Paideia of the myth. In that struggle, as we have seen, the positions changed more than once. The Homeric epic itself, with its free mythopoesis, was a feat of criticism in a situation of civilizational crisis. Hesiod's new truth had its point against the old myth including Homer. For the generation of the mystic philosophers both Homer and Hesiod had moved into the sphere of untruth, to which they opposed the truth of wisdom, of the soul and its depth. Aeschylus created the dramatic myth of the soul, superseding the epic myth in general. For Plato, finally, the tragedy and comedy of the fifth century became as untrue as Homer from whom the chain of Hellenic poetry descended. The discovery of the soul, as well as the struggle for its order, thus, is a process that extends through centuries and passes through more than one phase until it reaches its climax in the soul of Socrates and his impact on Plato. The attack on mimetic poetry from Homer to the time of Socrates pronounces no more than the plain truth that the Age of the Myth is closed. In Socrates the soul of man has at last found itself. After Socrates, no myth is possible. Except, perhaps, the Platonic myth, created through integration of the old form into the new, and functioning only as part of the symbolic form of the dialogue. Thus is outlined the differentiating consciousness' gradual approximation to truth. (Note however that Aeschylus and the mystic philosophers of Presocratic time represent two parallel strands of differentiation proceeding from Hesiod, while Plato's dialogues represent the unification of these two strands.) The reason for Plato's "totalitarianism": the cosmological perspective We have seen that only when the philosopher as king imposes the politeia in his soul on society can the polis come to be in the right order. The philosopher not only forms himself in order in accordance with the order of nature (the law of nature, the idea), but also, when ruling, forms the order of the interior of his fellow citizens and so of the polis, becoming a "craftsman of moderation, justice, and demotic virtue as a whole" (δημιουργον σωφροσύνης τε και δικαιοσύνης και συμπάσης της δημοτικης αρετης; 500 d 6). Plato acquires the most explicit look of a totalitarian when he has Socrates discuss how the imposition or the crafting is to be done. The philosopher needs to take the city and the dispositions (ηθη) of human beings as though they were a tablet, wipe it clean, and start over (501 a 2). For this purpose he should send the whole population over ten years of age (who are no longer impressionable) out of the polis to the country side, and take over the children under ten years of age who can still be molded from afresh.

Also to be practiced is eugenics -- the euthanasia of babies of ill-birth and the breeding of superior babies through the mating of the best at the most appropriate time (i.e. in harmony with the numerological structure of the cosmos). This is the project of the creation of the New Man which the fascists and the communists are to implement two millennia later (most notably, Khmer Rouge). Does Plato provide a justification for these utopian revolutionaries? In regard precisely to this proposal of the banishment of the adults and the taking-over of the young, Voegelin remarks: